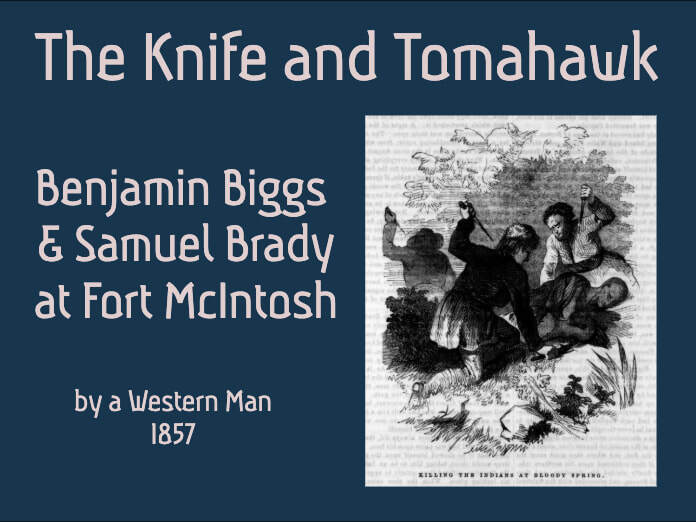

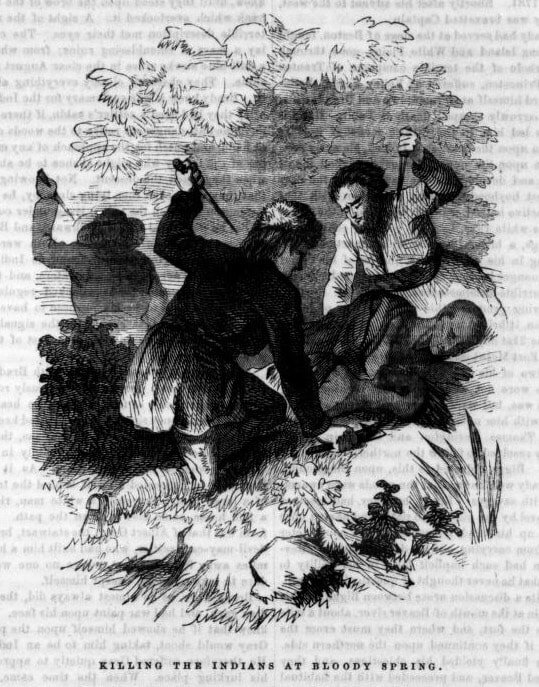

When the pursuit began, it must have been two o’clock, at least two hours had been consumed by the spies in making the necessary exploration about the house, ere they approached it, and in examining the ruins. Not a word was spoken upon the route by any one. Their leader kept steadily in advance. Occasionally he would diverge from the track, but only to take it up again a mile or so in advance. The Captain’s intimate knowledge of the topography of the country, enabled him to anticipate what points they would make. Thus he gained rapidly upon them by proceeding more nearly in a straight line toward the point at which they aimed to cross Beaver River.

At last, convinced from the general direction in which the trail led, that he could divine with absolute certainty the spot where they would ford that stream, he abandoned it and struck boldly across the country. The accuracy of his judgment was vindicated by the fact, that from an elevated crest of a long line of hills, he saw the Indians with their victims just disappearing up a ravine on the opposite side of the Beaver. He counted them as they slowly filed away under the rays of the declining sun. There were thirteen warriors, eight of whom were mounted—another woman, besides Gray’s wife, was in the cavalcade, and two children besides his—in all, five children.

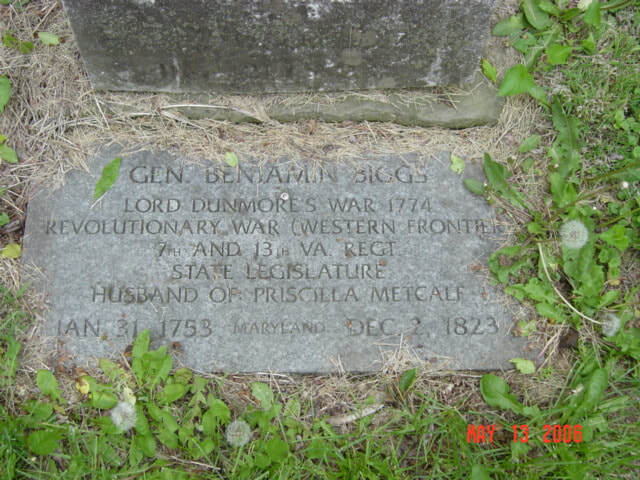

The odds seemed fearful to Biggs and Bevington; although Brady made no comments. The moment they had passed out of sight, Brady again pushed forward with unflagging energy, nor did his followers hesitate. There was not a man among them whose muscles were not tenseand rigid as whip-cord, from exercise and training, from hardship and exposure. Gray’s whole form seemed to dilate into twice its natural size at the sight of his wife and children. Terrible was the vengeance he swore.

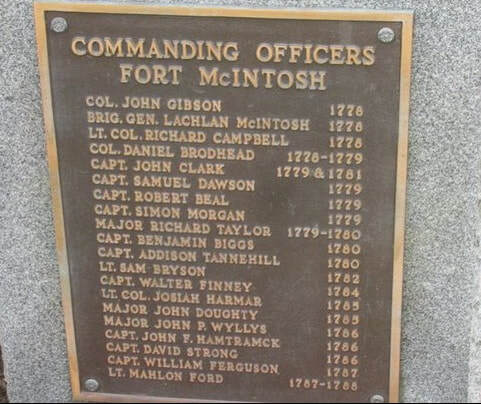

Just as the sun set, the spies forded the stream and began to ascend the ravine. It was evident that the Indians intended to camp for the night some distance up a small creek or run, which debouches into Beaver River, about three miles from the location of Fort McIntosh, and two below the ravine. The spot, owing to the peninsular form of the tongue of the land lying west of the Beaver, at which they expected to encamp, was full ten miles from that fort. Here there was a famous spring, so deftly and cunningly situated in a deep dell, and so densely inclosed with thick mountain pines, that there was little danger of discovery! Even they might light a fire and it could not be seen one hundred yards.

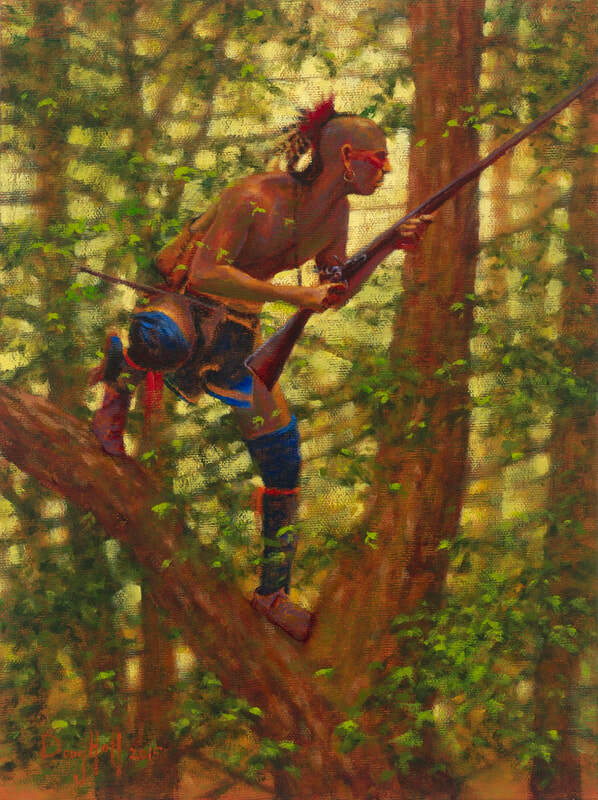

The proceedings of their leader, which would have been totally inexplicable to all others, were partially, if not fully, understood by his followers. At least, they did not hesitate or question him. When dark came, Brady pushed forward with as much apparent certainty as he had done during the day. So rapid was his progress, that the Indians had but just kindled their fire and cooked their meal, when their mortal foe, whose presence they dreaded as much as that of the small-pox, stood upon a huge rock looking down upon them.

His party had been left a short distance in the rear, at a convenient spot, whilst he went forward to reconnoitre. There they remained impatiently for three mortal hours. They discussed in low tones the extreme disparity of the force—the propriety of going to McIntosh to get assistance. But all agreed that if Brady ordered them to attack, success was certain. However impatient they were, he returned at last.