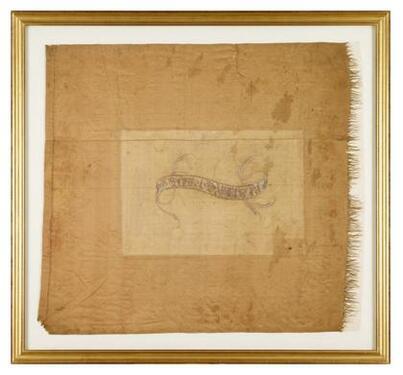

The sword believed to have been given by William Darke to George Washington. (CivilWarTalk.com)

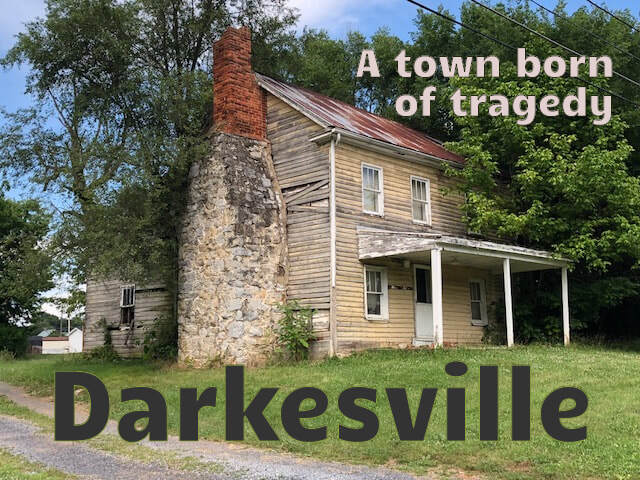

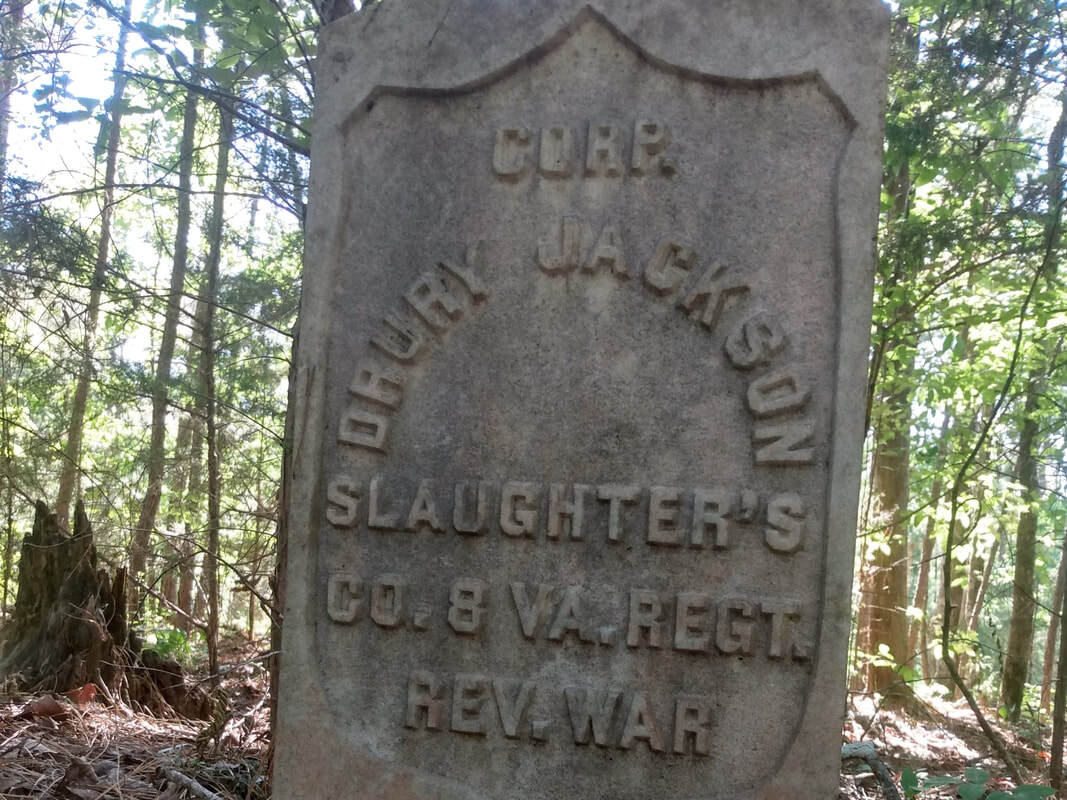

In the largest battle ever fought between Native Americans and European Americans, the “whites” lost—miserably. At the Battle of Wabash, in 1791, more than a thousand Americans were killed or wounded. (This puts the much more famous Battle of Little Big Horn--“Custer’s Last Stand”, where about 270 U.S. soldiers died--into context.) Reputations were ruined, too. The only reputation that seems to have survived intact was that of Lt. Colonel William Darke, a veteran of the 8th Virginia Regiment of Foot. During the battle, Darke saw his own son take a wound that would kill him after several days of agony.

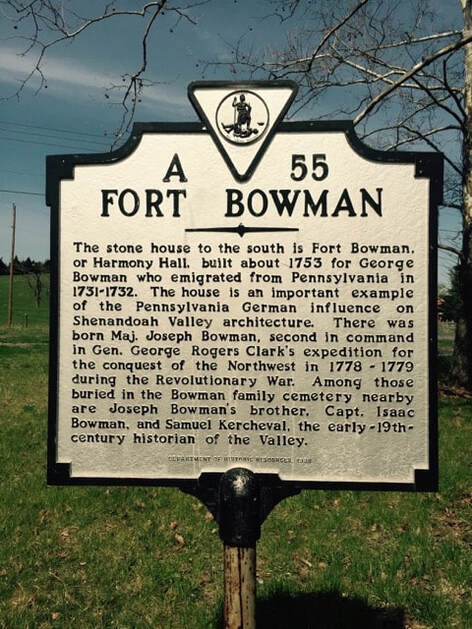

Darke is a poorly remembered hero of the American frontier. He served in virtually every frontier conflict from the French and Indian War to the Whiskey Rebellion. He was among the first captains to recruit a company for the 8th Virginia in 1776 and was captured at the Battle of Germantown a year-and-a-half later.

Darke is a poorly remembered hero of the American frontier. He served in virtually every frontier conflict from the French and Indian War to the Whiskey Rebellion. He was among the first captains to recruit a company for the 8th Virginia in 1776 and was captured at the Battle of Germantown a year-and-a-half later.

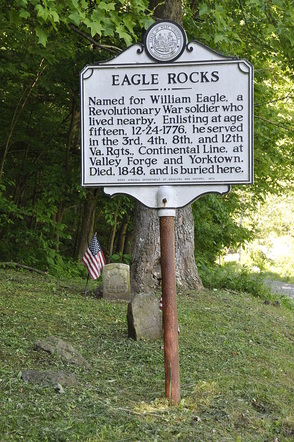

After a prisoner exchange he immediately recruited a regiment of frontier militia and was present for the victory at Yorktown. An Ohio county and a West Virginia town are named after him. He was well-known to George Washington, who personally asked him to serve in General Arthur St. Clair’s army of 1791.

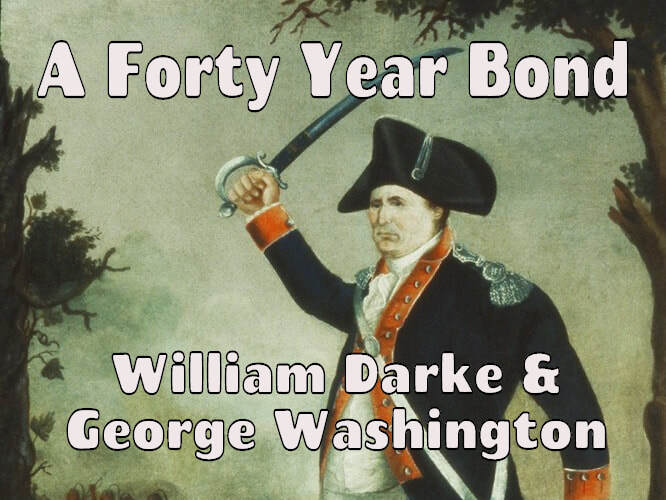

Washington clearly knew Darke and respected him. They may have served together in General Braddock’s army in 1755—though this is unproven and seems unlikely. If they served together in the French and Indian War it was more likely during the less well-known frontier conflicts that followed, when Darke served as a ranger. After the revolution, they had a business relationship though the Potomac Company, formed by Washington and others to make that river navigable. Darke Visited Mount Vernon in 1786 and 1787. Washington visited with Darke near the latter’s home close to Harper’s Ferry in 1790. In 1791, Washington wrote to Darke asking him to recruit officers for St. Clair’s army in advance of the campaign to pacify the Indians in Ohio. In that letter Washington bluntly and unapologetically told Darke that he was his third choice to command a regiment—pending a reply from his second choice (his first choice was “Light Horse Harry” Lee, who declined).

Intriguingly, what may be the best evidence of a close (but certainly unequal) relationship between Darke and Washington is a gift. According to longstanding tradition—apparently perpetuated by descendants of Washington’s nephew—Darke presented Washington with a sword. The date of the presentation is unknown, but it is believed by at least one researcher to have been worn by Washington at his presidential inauguration. The sword itself is real—it is on display at the Washington’s Headquarters Museum in Morristown, New Jersey.

Washington clearly knew Darke and respected him. They may have served together in General Braddock’s army in 1755—though this is unproven and seems unlikely. If they served together in the French and Indian War it was more likely during the less well-known frontier conflicts that followed, when Darke served as a ranger. After the revolution, they had a business relationship though the Potomac Company, formed by Washington and others to make that river navigable. Darke Visited Mount Vernon in 1786 and 1787. Washington visited with Darke near the latter’s home close to Harper’s Ferry in 1790. In 1791, Washington wrote to Darke asking him to recruit officers for St. Clair’s army in advance of the campaign to pacify the Indians in Ohio. In that letter Washington bluntly and unapologetically told Darke that he was his third choice to command a regiment—pending a reply from his second choice (his first choice was “Light Horse Harry” Lee, who declined).

Intriguingly, what may be the best evidence of a close (but certainly unequal) relationship between Darke and Washington is a gift. According to longstanding tradition—apparently perpetuated by descendants of Washington’s nephew—Darke presented Washington with a sword. The date of the presentation is unknown, but it is believed by at least one researcher to have been worn by Washington at his presidential inauguration. The sword itself is real—it is on display at the Washington’s Headquarters Museum in Morristown, New Jersey.