The Battle of Musgrove's Mill, 1780

John Buchanan (Westholme, 2022)

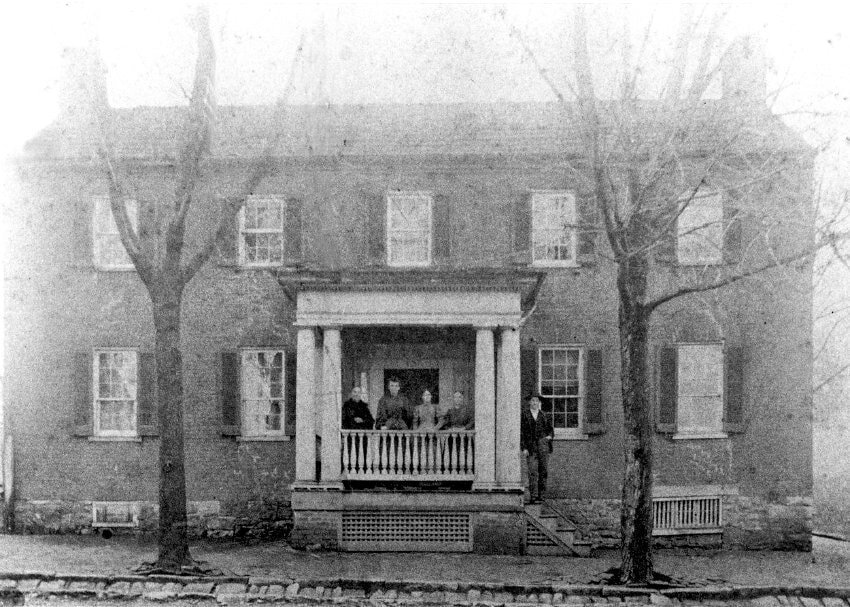

Fallen gravestones in a Rockingham County cemetery.

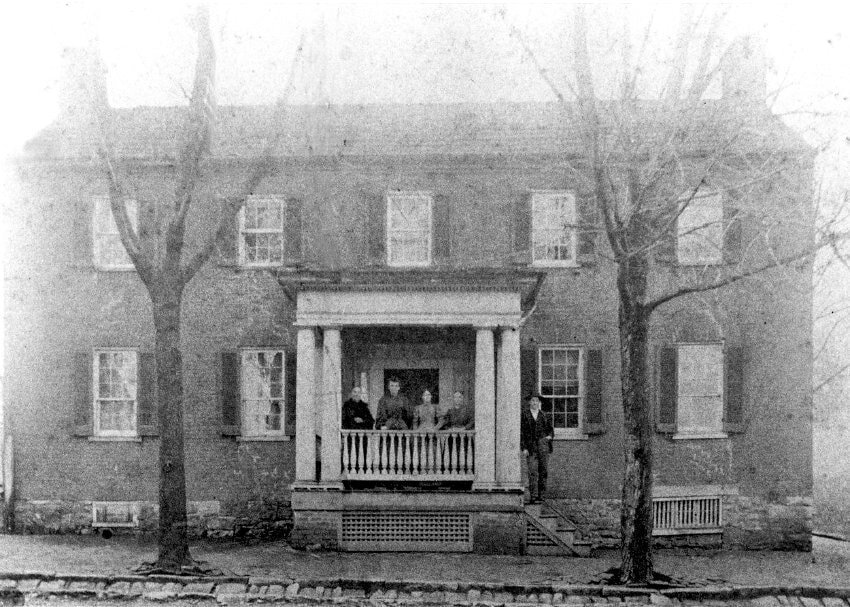

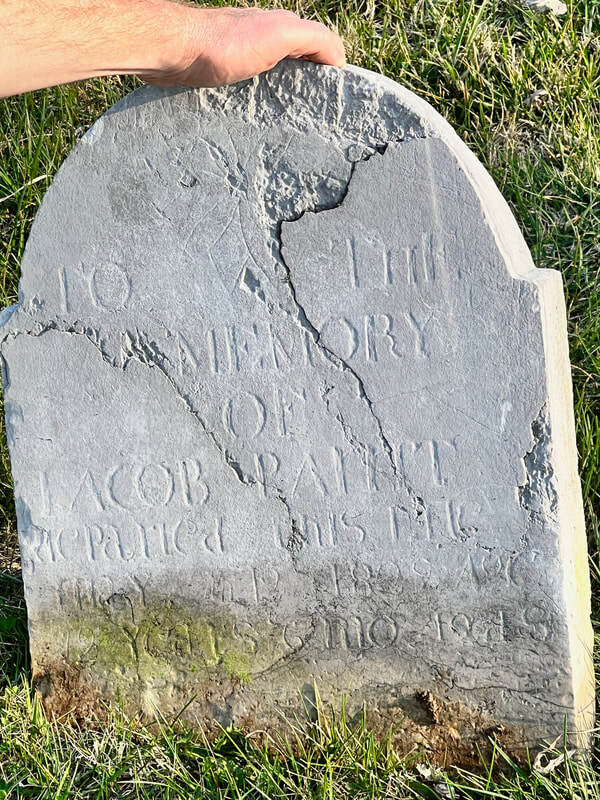

The grave of Lt. Jacob Parrot has a broke base and has been removed from the ground. The 200-year-old marker appears to have been made by an amateur craftsman and is now barely legible.

Angled into the light of a low sun, the inscription on Parrot's headstone is legible.

Jacob Parrot (1843-1908) was the first Civil War-era recipient of the Medal of Honor.

The grave of Rachel Parrot remains firmly placed in the ground.

Abraham Hornback was a marksman from Hampshire County picked from the 8th Virginia to serve in Morgan's Rifles. Gravestones have been installed for him in Indiana and Illinois, one of which is obviously in error. He isn't the only one.

Religious Liberty and the American Founding

Vincent Phillip Muñoz (University of Chicago Press, 2022)

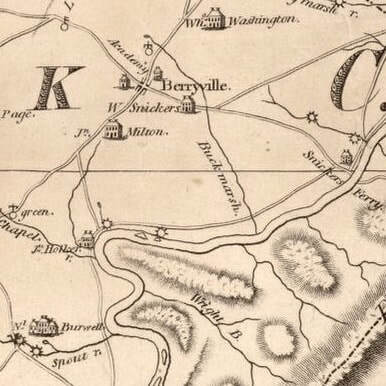

An imprecise 19th century map shows Berryville and the Shenandoah River. Buck Marsh Creek ran through Thomas Berry's property.

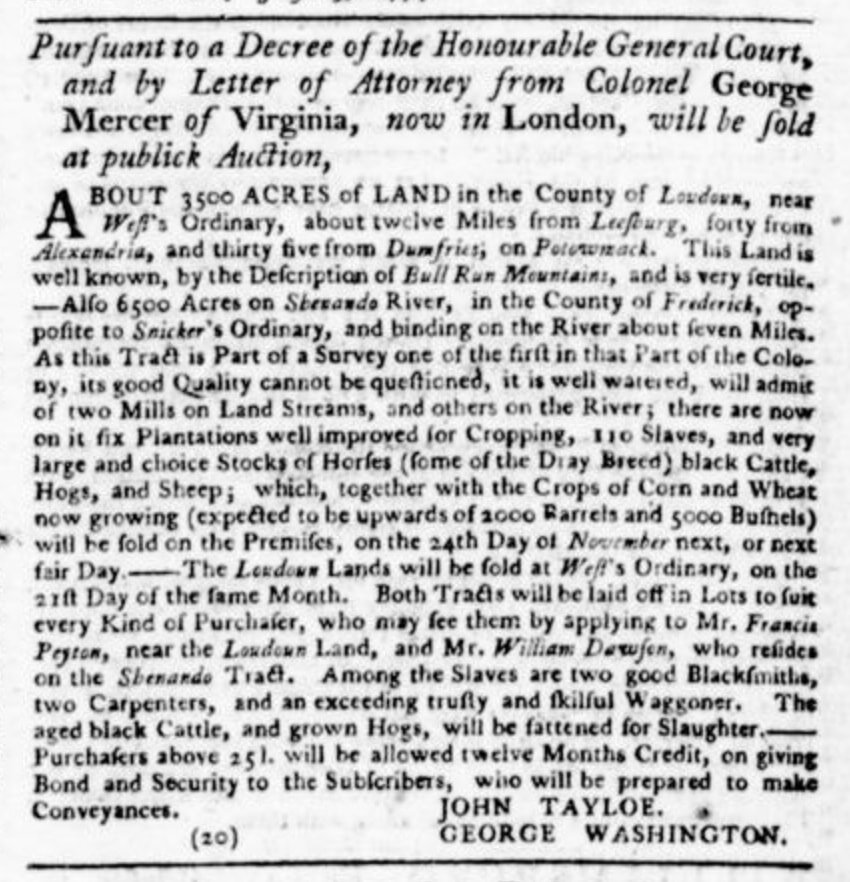

The auction notice in Purdie & Dixon's Virginia Gazette.

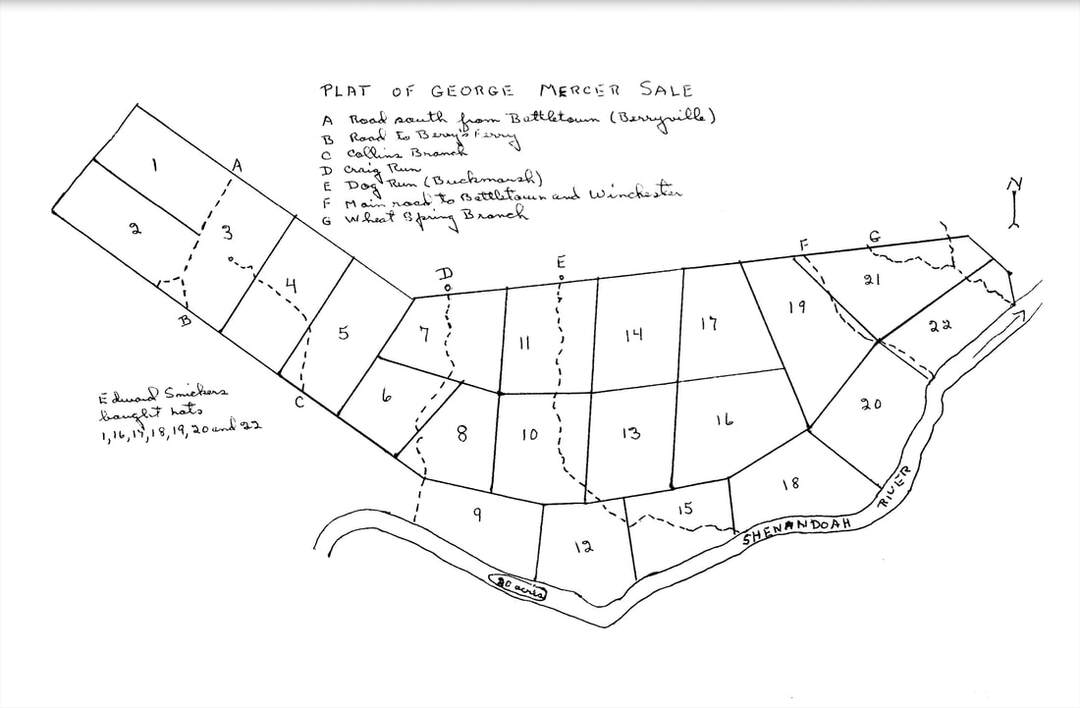

A sketch of the George Mercer plat made by Ingrid Jewell Jones in 1974 based on county records. Thomas Berry purchased lot 10 and the 20 acre island in the river. (Clarke County Historical Assn.)

A satellite image shows the clear outline of lot 10. Note especially it's V-shaped bottom. Berry's island appears to have grown considerably over 250 years.