In speaking these last words, the face of the speaker underwent, for a moment, a change, which told more than his story. The tone of scornful irony too, which accompanied the word protection, gave a new face to his character. As I marked the slight flush of his pale and somewhat withered cheek, the flash of his light blue eye, the curl of his lip, and a peculiar clashing of his eye-teeth as he spoke; I thought I had rarely seen a man, with whom it might not be as safe to trifle.

The day was now far spent; and as the sun descended, we had the satisfaction to observe that he sank behind a grove, that marked the course of a small branch of the Wabash, on the bank of which stood the house where we expected to find food and rest.

None but a western traveller can understand the entire satisfaction with which the daintiest child of luxury learns to look forward to the rude bed and homely fare, which await him, at the end of a hard day's ride, in the infant settlements. There is commonly a cabin of rough unhewn logs, containing one large room, where all the culinary operations of the family are performed, at the huge chimney around which the guests are ranged. The fastidious, who never wait to be hungry, may turn up their noses at the thought of being, for an hour before hand, regaled with the steam of their future meal. But to the weary and sharp set, there is something highly refreshing to the spirits and stimulating to the appetite. The dutch oven, well filled with biscuit, is no sooner discharged of them, than their place is occupied by sundry slices of bacon, which are immediately followed by eggs, broken into the hissing lard. In the mean time, a pot of strong coffee is boiling on a corner of the hearth; the table is covered with a coarse clean cloth; the butter and cream and honey are on it; and supper is ready.

"Then horn for horn they stretch and strive."

It makes me hungry now to think of it; and I am tempted to take back my word and eat something, having just told my wife I wanted no supper. But it will not do. I have not rode fifty miles to-day, and my table is so trim and my room so snug that I have no appetite.

But it is only in the first stage of a settlement, that these things are found. By and by, mine host, having opened a larger farm, builds him a house, of frame-work or brick, the masonry and carpentry of which show the rude handy-work of himself and his sons. He now employs several hands, and the leavings of their dinner will do for the supper of any chance travellers in the evening. A round deep earthen dish, in which a bit of fat pork or lean salt beef, crowns a small mound of cold greens or turnips, with loaf bread baked a month ago, and a tin can of skimmed milk now form the travellers supper. It is vain to expostulate. Our host has no fear of competition. He has now located the whole point of wood land crossed by the road, and no one can come nearer to him, on either hand, than ten miles. Besides, he is now the "squire" of the neighborhood, with "eyes severe," and "fair round belly with fat bacon lined;" and why should not the daily food of a man of his consequence be good enough for a hungry traveller?

It was to a house of this latter description that we now came. No one came out to receive us. Why should they? We took off our own baggage, and found our way into the house as we might.

On entering, I was struck with the appearance of the party, as their figures glimmered through the mingled lights of a dull window and a dim fire. Each individual, though seated, (and no man moved or bad us welcome) wore his hat, of shadowy dimensions; a sort of family resemblance, both in cut and color, ran through the dresses of all; and a like resemblance in complexion and cast of countenance marked all but one. This one, as we afterwards found, was the master of the mansion, a man of massive frame, and fat withal, but whose full cheeks, instead of the ruddy glow of health, were overcast with an ashy, dusky, money-loving hue. In the appearance of all the rest there was something ascetic and mortified. But landlord and guest wore all one common expression of ostentatious humility and ill-disguised self-complacency, which so often characterizes those new sects, that think they have just made some important discoveries in religion. Mine host was, as it proved, the Gaius of such a church, and his guests were preachers of the same denomination. I have forgotten the name; but they were not Quakers. I have been since reminded of them, on reading the description of the company Julian Peveril found at Bridgnorth's.

When we entered, our landlord was talking in a dull, plodding strain, and in a sort of solemn protecting tone, to his respectfully attentive guests. Our appearance made no interruption in his discourse; and he went on, addressing himself mainly to a raw looking youth, whose wrists and ankles seemed to have grown out of his sleeves and pantaloons since they were made. Where the light, which this young man was now thought worthy to diffuse, had broken in upon his own mind, I did not learn, but I presently discovered that he came from "a little east of sunrise," and had a curiosity as lively as my own, concerning the legends of the country.

"I guess brother P——," said he, "you have been so long in these parts, that it must have been right scary times when you first came here."

"Well! I cannot say," replied the other, "that there has been much danger in this country, since I came here. But if there was, it was nothing new to me. I was used to all that in Old Kentuck, thirty years ago."

"I should like," said the youth, "to hear something of your early adventures. I marvel that we should find any satisfaction in turning from the contemplation of God's peace, to listen to tales of blood and slaughter. But so it is. The old Adam will have a hankering after the things of this world."

"Well!" replied our host, "I have nothing very particular to tell. The scalping of three Indians, is all I have to brag of. And as to danger; except having the bark knocked off of my tree into my eyes, by a bullet, I do not know that I was ever in any mighty danger, but once."

"And when was that?"

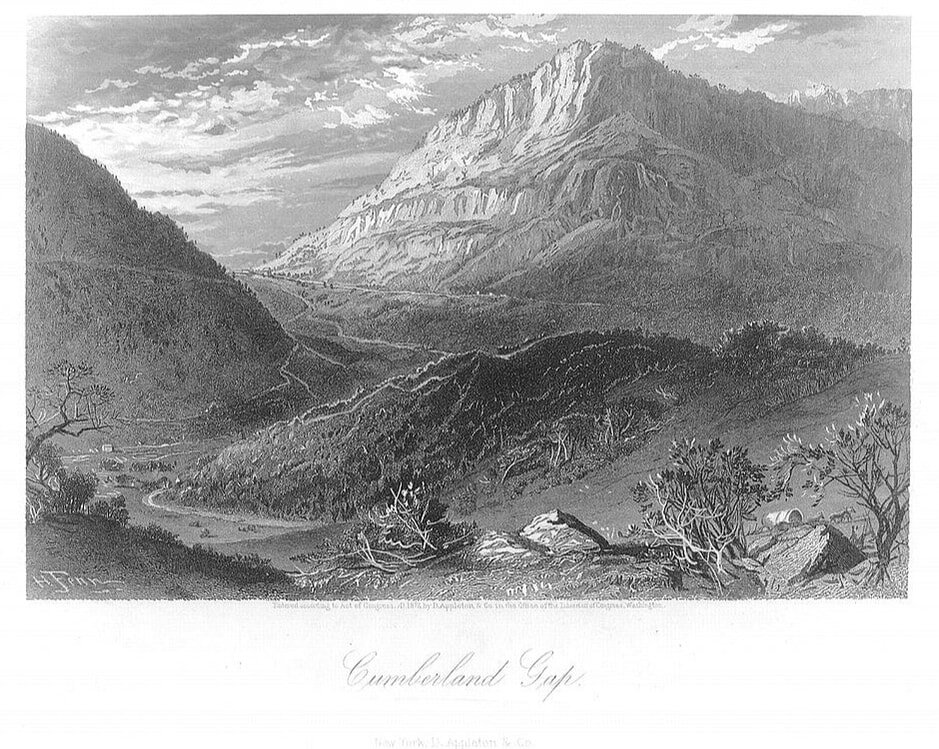

"Well! It was when we were moving out along the wilderness road. You see it was mighty ticklish times; so a dozen families of us started together, and we had regular guards, and scouts, and flankers, just like an army. The second day after we left Cumberland river, a couple of young fellows joined us, one by the name of Jones, and I do not remember the other's name. I suppose they had been living somewhere in Old Virginia, where they had plenty of slaves to wait on them; and it went hard with them to make their own fires, and cook their own victuals; so they were glad enough to fall in with us, and have us and our women to work and cook for them. But a man was a cash article there; and they both had fine horses and good guns; and, to hear them talk, (especially that fellow Jones,) you would have thought, two or three Indians before breakfast, would not have been a mouthful to them. We did not think much of them, but we told them, if they would take their turn in scouting and guarding, they were welcome to join us."

At this moment, our landlady, who was busy in a sort of shed, which adjoined the room we sat in, and served as a kitchen, entered, and stopping for a moment, heard what was passing. She was a good-looking woman, of about forty-five, with a meek subdued and broken hearted cast of countenance. I saw her look at her husband, and as she listened, her face assumed an expression of timid expostulation, mixed with that sort of wonderment, with which we regard a thing utterly unaccountable, but which use has rendered familiar.

Her lord and master caught the look, and bending his shaggy brow, said, "I guess the men will want their supper, by the time they get it."

She understood the hint, and stole away rebuked; uttering unconsciously, in a loud sigh, the long hoarded breath which she had held all the time she listened. Her manner was not intended to attract notice; but there was something in it, which disposed me to receive her husband's tale with some grains of allowance. He went on thus:

"The day we expected to get to the crab-orchard, it was their turn to bring up the rear. By good rights, they ought to have been a quarter of a mile or so behind us; and I suppose they were; when, all of a sudden, we heard the crack of a rifle, and here they come, right through us, and away they went. I looked round for my woman and I could not see her. The poor creature was a little behind, and thought there was no danger, because we all depended on them two fire eaters in the rear, to take care of stragglers. But when they ran off, you see, there was nobody between her and the Indians; and the first thing I saw, was her, running for dear life, and they after her. I set my triggers, and fixed myself to stop one of them; and just then, her foot caught in a grape vine, and down she came. I let drive at the foremost, and dropped him; but the other one ran right on. My gun was empty; and I had no chance but to put in, and try the butt of it. But I was not quite fast enough. He was upon her, and had his hand in her hair; and it was a mercy of God, he did not tomahawk her at once. He had plenty of time for that;—but he was too keen after the scalp; and, just as he was getting hold of his knife, I fetched him a clip that settled him. Just then, I heard a crack or two, and a ball whistled mighty near me; but, by this time, some of our party had rallied, and took trees; and that brought the Indians to a stand. So I put my wife behind a tree, and got one more crack at them; and then they broke and run. That was the only time I ever thought myself in any real danger, and that was all along of that Jones and the other fellow. But they made tracks for the settlement."

"Have you never seen Jones since?" said the mild voice of the courteous gentleman I have mentioned.

"No; I never have; and it's well for him; though, bless the Lord! I hope I could find in my heart now to forgive him. But if I had ever come across him, before I met with you, brother B——;" (addressing a grave senior of the party who received the compliment with impenetrable gravity;) "I guess it would not have been so well for him."

"Do you think you would know him again, if you were to see him?" said my companion.

"It's a long time ago," said he, "but I think I should. He was a mighty fierce little fellow, and had a monstrous blustering way of talking."

"Was he any thing like me?" said the stranger, in a low but hissing tone.

The man started, and so did we all, and gazed on the querist. In my life, I never saw such a change in any human face. The pale cheek was flushed, the calm eye glowed with intolerable fierceness, and every feature worked with loathing. But he commanded his voice, though the curl of his lip disclosed the full length of one eye tooth, and he again said, "look at me. Am not I the man?"

"I do not know that you are," replied the other doggedly, and trying in vain to lift his eye to that which glared upon him. "I do not know that you are?" muttered he.

"Where is he? where is he," screamed a female voice; "let me see him. I'll know him, bless his heart! I'll know him any where in the world."

Saying this, our landlady rushed into the circle, and stood among us, while we all rose to our feet. She looked eagerly around. Her eye rested a moment on the stranger's face; and in the next instant her arms were about his neck, and her head on his bosom, where she shed a torrent of tears.

I need not add, that the subject of the Landlord's tale, was the very incident which my companion had related on the road. He soon made his escape, cowed and chop-fallen; and the poor woman bustled about, to give us the best the house afforded, occasionally wiping her eyes, or stopping for a moment to gaze mutely and sadly on the generous stranger, who had protected her when deserted by him who lay in her bosom.

The grave brethren looked, as became them, quite scandalized, at this strange scene. It was therefore promptly explained to them; but the explanation dissipated nothing of the gloom of their countenances. Their manner to the poor woman was still cold and displeased, and they seemed to forget her husband's fault, in their horror at having seen her throw herself into the arms of a stranger. For my part, I thought the case of the good Samaritan in point, and could not help believing, that he who had decided that, would pronounce that her grateful affection had been bestowed where it was due.

Originally Published in the Southern Literary Messenger, 1:7 (1835), pp.336-340.