The Federal officials under whose authority these treaties were made had no idea of the complexity of the problem. In 1789 the Secretary of War, the New- Englander Knox, solemnly reported to the President that if the treaties were only observed and the Indians conciliated, they would become attached to the United States, and the expense of managing them for the next half-century would be only some fifteen thousand dollars a year. He probably represented not unfairly the ordinary Eastern view of the matter. He had not the slightest conception of the rate at which the settlements were increasing. Though he expected that tracts of Indian territory would from time to time be acquired, he made no allowance for a growth so rapid that within the half-century a dozen populous States were to stand within the Indian-owned wilderness of his day. He utterly failed to grasp the central feature of the situation, which was that the settlers needed the land, and were bound to have it within a few years, and that the Indians would not give it up, under no matter what treaty, without an appeal to arms.

As a matter of fact the red men were as little disposed as the white to accept a peace on any terms that were possible. The Secretary of War, who knew nothing of Indians by actual contact, wrote that it would be indeed pleasing “to a philosophic mind to reflect that, instead of exterminating a part of the human race by our modes of population . . . . we had imparted our knowledge of cultivation and the arts to the aboriginals of the country,” thus preserving and civilizing them; and the public men who represented districts remote from the frontier shared these views of large though vague beneficence. But neither the white frontiersmen nor their red antagonists possessed “philosophic minds.” They represented two stages of progress, ages apart, and it would have needed many centuries to bring the lower to the level of the higher. Both sides recognized the fact that their interests were incompatible, and that the question of their clashing rights had to be settled by the strong hand.

In the Northwest matters culminated sooner than in the Southwest. The Georgians and the settlers along the Tennessee and Cumberland were harassed rather than seriously menaced by the Creek war parties; but in the North the more dangerous Indians of the Miami, the Wabash, and the lakes gathered in bodies so large as fairly to deserve the name of armies. Moreover, the pressure of the white advance was far heavier in the North. The pioneers who settled in the Ohio basin were many times as numerous as those who settled on the lands west of the Oconee or north of the Cumberland, and were fed from States much more populous. The advance was stronger, the resistance more desperate; naturally the open break occurred where the strain was most intense.

There was fierce border warfare in the South. In the North there were regular campaigns, and pitched battles were fought between Federal armies as large as those commanded by Washington at Trenton or Greene at Eutaw Springs, and bodies of Indian warriors more numerous than had ever yet appeared on any single field.

The newly created government of the United States was very reluctant to make formal war on the Northwestern Indians. Not only were President Washington and the national Congress honorably desirous of peace, but they were hampered for funds, and dreaded any extra expense. Nevertheless, they were forced into war. Throughout the years 1789 and 1790 an increasing volume of appeals for help came from the frontier countries. The Governor of the Northwestern Territory, the Brigadier-General of the troops on the Ohio, the members of the Kentucky Convention, all the county lieutenants of Kentucky, the lieutenants of the frontier counties of Virginia proper, the representatives from the counties, the field officers of the different districts, the General Assembly of Virginia—all sent bitter complaints and long catalogues of injuries to the President, the Secretary of War, and the two Houses of Congress—complaints which were redoubled after Harmar’s failure. With heavy hearts the national authorities prepared for war. Their decision was justified by the redoubled fury of the Indian raids during the early part of 1791. Among others, the settlements near Marietta were attacked, a day or two after the new year began, in bitter winter weather. A dozen persons, including a woman and two children, were killed, and five men were taken prisoners. The New England settlers, though brave and hardy, were unused to Indian warfare. They were taken by surprise, and made no effective resistance; the only Indian hurt was wounded with a hatchet by the wife of a frontier hunter. There were some twenty-five Indians in the attacking party; they were Wyandots and Delawares, who had been mixing on friendly terms with the settlers throughout the preceding summer, and so knew how best to deliver the assault. The settlers had not only treated these Indians with much kindness, but had never wronged any of the red race, and had been lulled into a foolish feeling of security by the apparent good-will of the treacherous foes. The assault was made in the twilight on the 2d of January, the Indians crossing the frozen Muskingum, and stealthily approaching a blockhouse and two or three cabins. The inmates were frying meat for supper, and did not suspect harm, offering food to the Indians; but the latter, once they were within-doors, dropped the garb of friendliness, and shot or tomahawked all save a couple of men who escaped, and the five who were made prisoners. The captives were all taken to the Miami or Detroit, and, as usual, were treated with much kindness and humanity by the British officers and traders with whom they came in contact. McKee, the British Indian agent, who was always ready to incite the savages to war against the Americans as a nation, but who was quite as ready to treat them kindly as individuals, ransomed one prisoner; the latter went to his Massachusetts home to raise the amount of his ransom, and returned to Detroit to refund it to his generous rescuer. Another prisoner was ransomed by a Detroit trader, and worked out his ransom in Detroit itself. Yet another was redeemed from captivity by the famous Iroquois chief Brant, who was ever a terrible and implacable foe, but a greathearted and kindly victor. The fourth prisoner died, while the Indians took so great a liking to the fifth that they would not let him go, but adopted him into the tribe, made him dress as they did, and in a spirit of pure friendliness pierced his ears and nose. After Wayne’s treaty he was released, and returned to Marietta to work at his trade as a stone-mason, his bored nose and slit ears serving as mementos of his captivity.

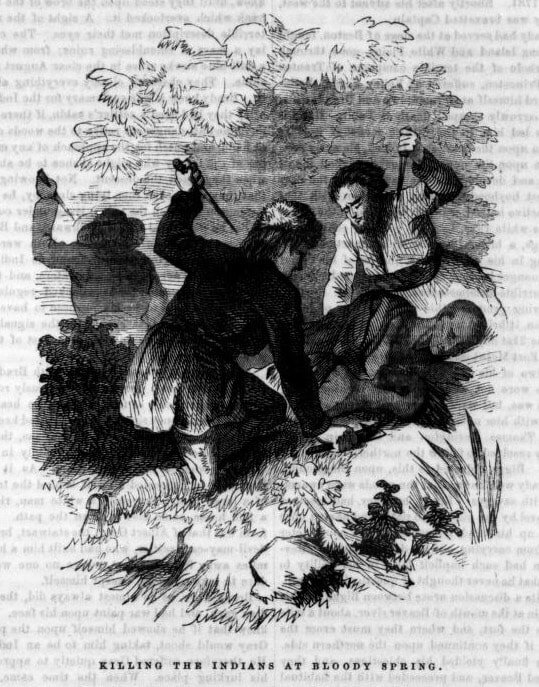

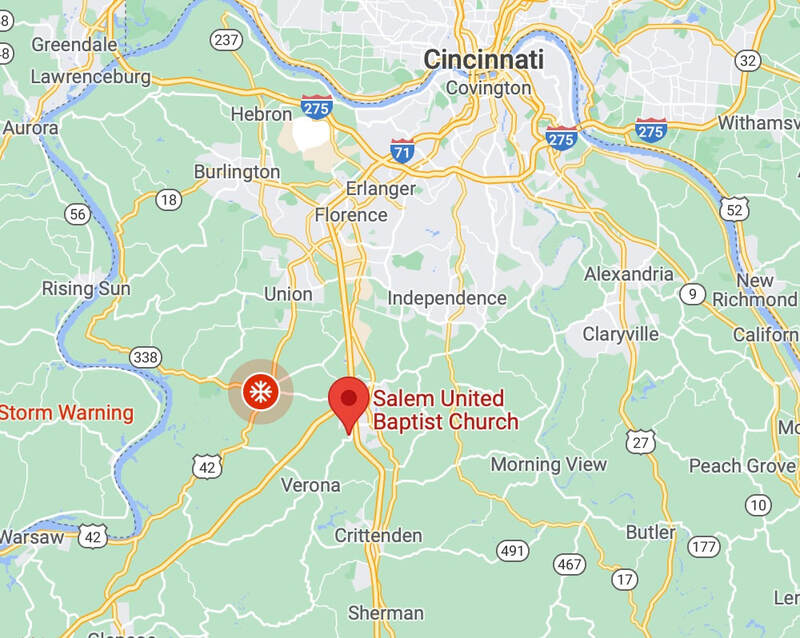

The squalid little town of Cincinnati also suffered from the Indian war parties in the spring of this year, several of the townsmen being killed by the savages, who grew so bold that they lurked through the streets at nights, and lay in ambush in the gardens where the garrison of Fort Washington raised their vegetables. One of the Indian attacks, made upon a little palisaded “station” which had been founded by a man named Dunlop, some seventeen miles from Cincinnati, was noteworthy because of an act of not uncommon cruelty by the Indians. In the station there were some regulars. Aided by the settlers, they beat back their foes; whereupon the enraged savages brought one of their prisoners within ear-shot of the walls and tortured him to death. The torture began at midnight, and the screams of the wretched victim were heard until daylight.

Until this year the war was not general. One of the most bewildering problems to be solved by the Federal officers on the Ohio was to find out which tribes were friendly and which hostile. Many of the inveterate enemies of the Americans were as forward in professions of friendship as the peaceful Indians, and were just as apt to be found at the treaties, or lounging about the settlements; and this widespread treachery and deceit made the task of the army officers puzzling to a degree. As for the frontiersmen, who had no means whatever of telling a hostile from a friendly tribe, they followed their usual custom, and lumped all the Indians, good and bad, together, for which they could hardly be blamed. Even St. Clair, who had small sympathy with the backwoodsmen, acknowledged that they could not and ought not to submit patiently to the cruelties and depredations of the savages: “they are in the habit of retaliation, perhaps without attending precisely to the nations from which the injuries are received.” A long course of such aggressions and retaliations resulted, by the year 1791, in all the Northwestern Indians going on the war-path. The hostile tribes had murdered and plundered the frontiersmen; the vengeance of the latter, as often as not, had fallen on friendly tribes; and these justly angered friendly tribes usually signalized their taking the red hatchet by some act of treacherous hostility directed against settlers who had not molested them.

In the late winter of 1791 the hitherto friendly Delawares, who hunted or traded along the western frontiers of Pennsylvania and Virginia proper, took this manner of showing that they had joined the open foes of the Americans. A big band of warriors spread up and down the Alleghany for about forty miles, and on the 9th of February attacked all the outlying settlements. The Indians who delivered this attack had long been on intimate terms with the Alleghany settlers, who were accustomed to see them in and about their houses; and as the savages acted with seeming friendship to the last moment, they were able to take the settlers completely unawares, so that no effective resistance was made. Some settlers were killed and some captured. Among the captives was a lad named John Brickell, who, though at first maltreated, and forced to run the gauntlet, was afterwards adopted into the tribe, and was not released until after Wayne’s victory. After his adoption he was treated with the utmost kindness, and conceived a great liking for his captors, admiring their many good qualities, especially their courage and their kindness to their children. Long afterwards he wrote down his experiences, which possess a certain value as giving from the Indian stand-point an account of some of the incidents of the forest warfare of the day.

The warriors who had engaged in this raid on their former friends, the settlers along the Alleghany, retreated two or three days’ journey into the wilderness to an appointed place, where they found their families. One of the Girtys was with the Indians. No sooner had the last of the warriors come in, with their scalps and prisoners, including the boy Brickell, than ten of their number deliberately started back to Pittsburg, to pass themselves as friendly Indians, and trade. In a fortnight they returned, laden with goods of various kinds, including whiskey. Some of the inhabitants, sore from disaster, suspected that these Indians were only masquerading as friendly, and prepared to attack them; but one of the citizens warned them of their danger, and they escaped. Their effrontery was as remarkable as their treachery and duplicity. They had suddenly attacked and massacred settlers by whom they had never been harmed, and with whom they preserved an appearance of entire friendship up to the very moment of the assault. Then, their hands red with the blood of their murdered friends, they came boldly into Pittsburg, among the near neighbors of these same murdered men, and stayed there several days to trade, pretending to be peaceful allies of the whites. With savages so treacherous and so ferocious it was a mere impossibility for the borderers to distinguish the hostile from the friendly, as they hit out blindly to revenge the blows that fell upon them from unknown hands. Brutal though the frontiersmen often were, they never employed the systematic and deliberate bad faith which was a favorite weapon with even the best of the red tribes.

The people who were out of reach of the Indian tomahawk, and especially the Federal officers, were often unduly severe in judging the borderers for their deeds of retaliation. Brickell’s narrative shows that the parties of seemingly friendly Indians who came in to trade were sometimes—and, indeed, in this year 1791 it is probable they were generally—composed of Indians who were engaged in active hostilities against the settlers, and who were always watching for a chance to murder and plunder. On March 9th, a month after the Delawares had begun their attacks, the grim backwoods Captain Brady, with some of his Virginian rangers, fell on a party of them who had come to a block-house to trade, and killed four. The Indians asserted that they were friendly, and both the Federal Secretary of War and the Governor of Pennsylvania denounced the deed and threatened the offenders; but the frontiersmen stood by them. Soon afterwards a delegation of chiefs from the Seneca tribe of the Iroquois arrived at Fort Pitt and sent a message to the President complaining of the murder of these alleged friendly Indians. On the very day these Seneca chiefs started on their journey home another Delaware war party killed nine settlers, men, women, and children, within twenty miles of Fort Pitt, which so enraged the people of the neighborhood that the lives of the Senecas were jeopardized. The United States authorities were particularly anxious to keep at peace with the Six Nations, and made repeated efforts to treat with them; but the Six Nations stood sullenly aloof, afraid to enter openly into the struggle, and yet reluctant to make a firm peace or cede any of their lands.

The intimate relations between the Indians and the British at the lake posts continued to perplex and anger the Americans. While the frontiers were being mercilessly ravaged, the same Indians who were committing the ravages met in council with the British agent, Alexander McKee, at the Miami Rapids, the council being held in this neighborhood for the special benefit of the very towns which were most hostile to the Americans, and which had been partially destroyed by Harmar the preceding fall. The Indian war was at its height, and the murderous forays never ceased throughout the spring and summer. McKee came to Miami in April, and was forced to wait nearly three months, because of the absence of the Indian war party, before the principal chiefs and head men gathered to meet him. At last, on July 1st, they were all assembled; not only the Shawnees, Delawares, Wyandots, Ottawas, Pottawattamies, and others who had openly taken the hatchet against the Americans, but also representatives of the Six Nations, and tribes of savages from lands so remote that they carried no guns, but warred with bows, spears, and tomahawks, and were clad in buffalo-robes instead of blankets. McKee in his speech to them did not incite them to war. On the contrary, he advised them, in guarded language, to make peace with the United States, but only upon terms consistent with their “honor and interest.” He assured them that, whatever they did, he wished to know what they desired, and that the sole purpose of the British was to promote the welfare of the confederated Indians. Such very cautious advice was not of a kind to promote peace; and the goods furnished the savages at the council included not only cattle, corn, and tobacco, but also quantities of powder and balls.

The chief interest of the British was to preserve the fur trade for their merchants, and it was mainly for this reason that they clung so tenaciously to the lake posts. For their purposes it was essential that the Indians should remain lords of the soil. They preferred to see the savages at peace with the Americans, provided that in this way they could keep their lands; but, whether through peace or war, they wished the lands to remain Indian, and the Americans to be barred from them. While they did not at the moment advise war, their advice to make peace was so faintly uttered and so hedged round with conditions as to be of no weight, and they furnished the Indians not only with provisions, but with munitions of war. While McKee and other British officers were at the Miami Rapids, holding councils with the Indians and issuing to them goods and weapons, bands of braves were continually returning from forays against the American frontier, bringing in scalps and prisoners; and the wilder subjects of the British King, like the Girtys, and some of the French from Detroit, went off with the war parties on their forays. The authorities at the capital of the new republic were deceived by the warmth with which the British insisted that they were striving to bring about a peace; but the frontiersmen were not deceived, and they were right in their belief that the British were really the mainstay and support of the Indians in their warfare.

Peace could only be won by the unsheathed sword. Even the national government was reluctantly driven to this view. As all the Northwestern tribes were banded in open war, it was useless to let the conflict remain a succession of raids and counter-raids. Only a severe stroke delivered by a formidable army could cow the tribes. It was hopeless to try to deliver such a crippling blow with militia alone, and it was very difficult for the infant government to find enough money or men to equip an army composed exclusively of regulars. Accordingly preparations were made for a campaign with a mixed force of regulars, special levies, and militia; and St. Clair, already Governor of the Northwestern Territory, was put in command of the army as Major-General.

Before the army was ready the Federal government was obliged to take other measures for the defence of the border. Small bodies of rangers were raised from among the frontier militia, being paid at the usual rate for soldiers in the army—a net sum of about two dollars a month while in service. In addition, on the repeated and urgent request of the frontiersmen, a few of the most active hunters and best woodsmen, men like Brady, were enlisted as scouts, being paid six or eight times the ordinary rate. These men, because of their skill in woodcraft and their thorough knowledge of Indian fighting, were beyond comparison more valuable than ordinary militia or regulars, and were prized very highly by the frontiersmen.

Besides thus organizing the local militia for defence, the President authorized the Kentuckians to undertake two offensive expeditions against the Wabash Indians, so as to prevent them from giving aid to the Miami tribes, whom St. Clair was to attack. Both expeditions were carried on by bands of mounted volunteers, such as had followed Clark on his various raids. The first was commanded by Brigadier-General Charles Scott; Colonel John Hardin led his advance-guard, and Wilkinson was second in command. Towards the end of May, Scott crossed the Ohio at the head of eight hundred horse-riflemen, and marched rapidly and secretly towards the Wabash towns. A mounted Indian discovered the advance of the Americans, and gave the alarm, and so most of the Indians escaped just as the Kentucky riders fell on the towns. But little resistance was offered by the surprised and outnumbered savages. Only five Americans were wounded, while of the Indians thirty-two were slain, as they fought or fled, and forty-one prisoners, chiefly women and children, were brought in, either by Scott himself, or by his detachments under Hardin and Wilkinson. Several towns were destroyed, and the growing corn cut down. There were not a few French living in the towns, in well-finished log houses, which were burned with the wigwams. The second expedition was under the command of Wilkinson, and consisted of over five hundred men. He marched in August, and repeated Scott’s feat, again burning down two or three towns, and destroying the goods and the crops. He lost three or four men killed or wounded, but killed ten Indians and captured some thirty. In both expeditions the volunteers behaved well, and committed no barbarous act, except that in the confusion of the actual onslaught a few non-combatants were slain. The Wabash Indians were cowed and disheartened by their punishment, and in consequence gave no aid to the Miami tribes; but beyond this the raids accomplished nothing, and brought no nearer the wished-for time of peace. Meanwhile St. Clair was striving vainly to hasten the preparations for his own far more formidable task. There was much delay in forwarding him the men and the provisions and munitions. Congress hesitated and debated; the Secretary of War, hampered by a newly created office and insufficient means, did not show to advantage in organizing the campaign, and was slow in carrying out his plans, while there was positive dereliction of duty on the part of the quartermaster, and the contractors proved both corrupt and inefficient. The army was often on short commons, lacking alike food for the men and fodder for the horses; the powder was poor, the axes useless, the tents and clothing nearly worthless, while the delays were so extraordinary that the troops did not make the final move from Fort Washington until mid-September.

St. Clair himself was broken in health; he was a sick, weak, elderly man, high-minded, and zealous to do his duty, but totally unfit for the terrible responsibilities of such an expedition against such foes. The troops were of wretched stuff. There were two small regiments of regular infantry, the rest of the army being composed of six months levies and of militia ordered out for this particular campaign. The pay was contemptible. Each private was given three dollars a month, from which ninety cents were deducted, leaving a net payment of two dollars and ten cents a month. Sergeants netted three dollars and sixty cents, while the lieutenants received twenty-two, the captains thirty, and the colonels sixty dollars. The mean parsimony of the nation in paying such low wages to men about to be sent on duties at once very arduous and very dangerous met its fit and natural reward. Men of good bodily powers and in the prime of life, and especially men able to do the rough work of frontier farmers, could not be hired to fight Indians in unknown forests for two dollars a month. Most of the recruits were from the streets and prisons of the seaboard cities. They were hurried into a campaign against peculiarly formidable foes before they had acquired the rudiments of a soldier’s training, and of course they never even understood what woodcraft meant. The officers were men of courage, as in the end most of them showed by dying bravely on the field of battle, but they were utterly untrained themselves, and had no time in which to train their men. Under such conditions it did not need keen vision to foretell disaster. Harmar had learned a bitter lesson the preceding year; he knew well what Indians could do and what raw troops could not, and he insisted with emphasis that the only possible outcome to St. Clair’s expedition was defeat.

As the raw troops straggled to Pittsburg they were shipped down the Ohio to Fort Washington; and St. Clair made the headquarters of his army at a new fort some twenty-five miles northward, which he christened Fort Hamilton. During September the army slowly assembled two small regiments of regulars, two of six months levies, a number of Kentucky militia, a few cavalry, and a couple of small batteries of light guns. After wearisome delays, due mainly to the utter inefficiency of the quartermaster and contractor, the start for the Indian towns was made on October the 4th. The army trudged slowly through the deep woods and across the wet prairies, cutting out its own road, and making but five or six miles a day. On October 13th a halt was made to build another little fort, christened in honor of Jefferson. There were further delays, caused by the wretched management of the commissariat department, and the march was not resumed until the 24th, the numerous sick being left in Fort Jefferson. Then the army once more stumbled northward through the wilderness. The regulars, though mostly raw recruits, had been reduced to some kind of discipline, but the six months levies were almost worse than the militia. Owing to the long delays, and to the fact that they had been enlisted at various times, their terms of service were expiring day by day, and they wished to go home, and tried to, while the militia deserted in squads and bands. Those that remained were very disorderly. Two who attempted to desert were hanged, and another, who shot a comrade, was hanged also; but even this severity in punishment failed to stop the demoralization.

With such soldiers there would have been grave risk of disaster under any commander, but St. Clair’s leadership made the risk a certainty. There was Indian sign, old and new, all through the woods, and the scouts and stragglers occasionally interchanged shots with small parties of braves, and now and then lost a man killed or captured. It was therefore certain that the savages knew every movement of the army, which, as it slowly neared the Miami towns, was putting itself within easy striking range of the most formidable Indian confederacy in the Northwest. The density of the forest was such that only the utmost watchfulness could prevent the foe from approaching within arm’s-length unperceived. It behooved St. Clair to be on his guard, and he had been warned by Washington, who had never forgotten the scenes of Braddock’s defeat, of the danger of a surprise. But St. Clair was broken down by the worry and by continued sickness; time and again it was doubtful whether he could do so much as stay with the army. The second in command, Major-General Richard Butler, was also sick most of the time, and, like St. Clair, he possessed none of the qualities of leadership save courage, The whole burden fell on the Adjutant-General, Colonel Winthrop Sargent, an old Revolutionary officer; without him the expedition would probably have failed in ignominy even before the Indians were reached; and he showed not only cool courage, but ability of a good order; yet in the actual arrangements for battle he was of course unable to remedy the blunders of his superiors.

St. Clair should have covered his front and flanks for miles around with scouting parties; but he rarely sent any out, and, thanks to letting the management of those that did go devolve on his subordinates, and to not having their reports made to him in person, he derived no benefit from what they saw. He had twenty Chickasaws with him, but he sent these off on an extended trip, lost touch of them entirely, and never saw them again until after the battle. He did not seem to realize that he was himself in danger of attack. When some fifty miles or so from the Miami towns, on the last day of October, sixty of the militia deserted; and he actually sent back after them one of his two regular regiments, thus weakening by one-half the only trustworthy portion of his force.

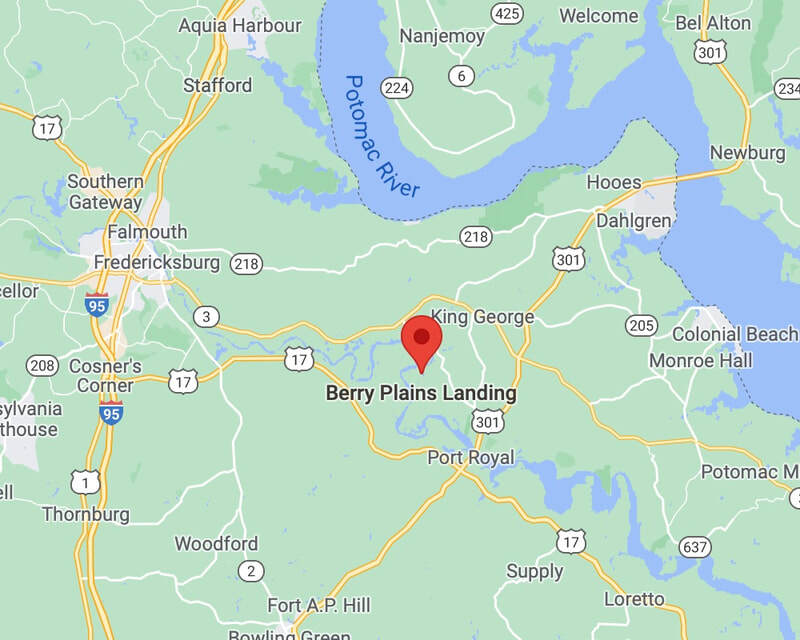

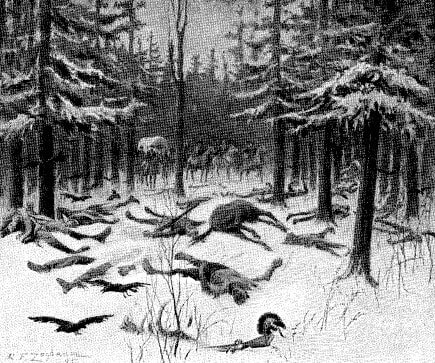

On November 3d the doomed army, now reduced to a total of about fourteen hundred men, camped on the eastern fork of the Wabash, high up, where it was but twenty yards wide. There was snow on the ground, and the little pools were skimmed with ice. The camp was on a narrow rise of ground, where the troops were cramped together, the artillery and most of the horse in the middle. On both flanks and along most of the real the ground was low and wet. All about the wintry woods lay in frozen silence. In front the militia were thrown across the creek, and nearly a quarter of a mile beyond the rest of the troops. Parties of Indians were seen during the afternoon, and they skulked around the lines at night, so that the sentinels frequently fired at them; yet neither St. Clair nor Butler took any adequate measures to ward off the impending blow. It is improbable that, as things actually were at this time, they could have won a victory over their terrible foes, but they might have avoided overwhelming disaster.

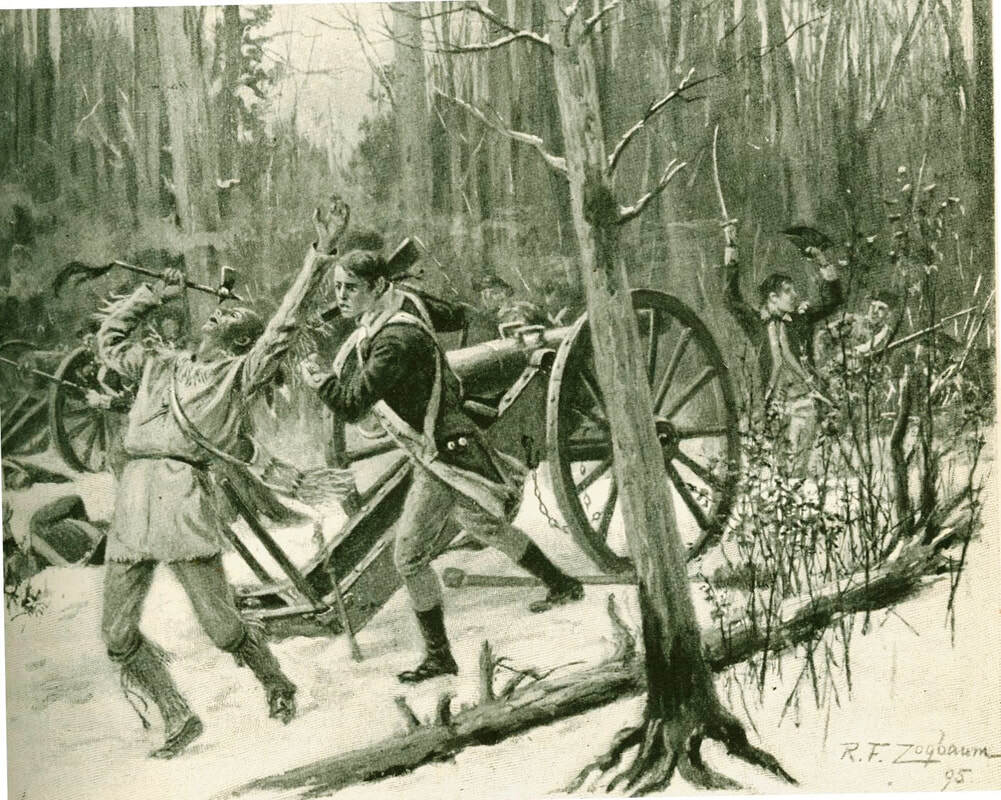

On November 4th the men were under arms, as usual, by dawn, St. Clair intending to throw up intrenchments and then make a forced march in light order against the Indian towns. But he was forestalled. Soon after sunrise, just as the men were dismissed from parade, a sudden assault was made upon the militia, who lay unprotected beyond the creek. The unexpectedness and fury of the onset, the heavy firing, and the wild whoops and yells of the throngs of painted savages threw the militia into disorder. After a few moments’ resistance they broke and fled in wild panic to the camp of the regulars, among whom they drove in a frightened herd, spreading dismay and confusion.

The drums beat, and the troops sprang to arms as soon as they heard the heavy firing at the front, and their volleys for a moment checked the onrush of the plumed woodland warriors. But the check availed nothing. The braves filed off to one side and the other, completely surrounded the camp, killed or drove in the guards and pickets, and then advanced close to the main lines.