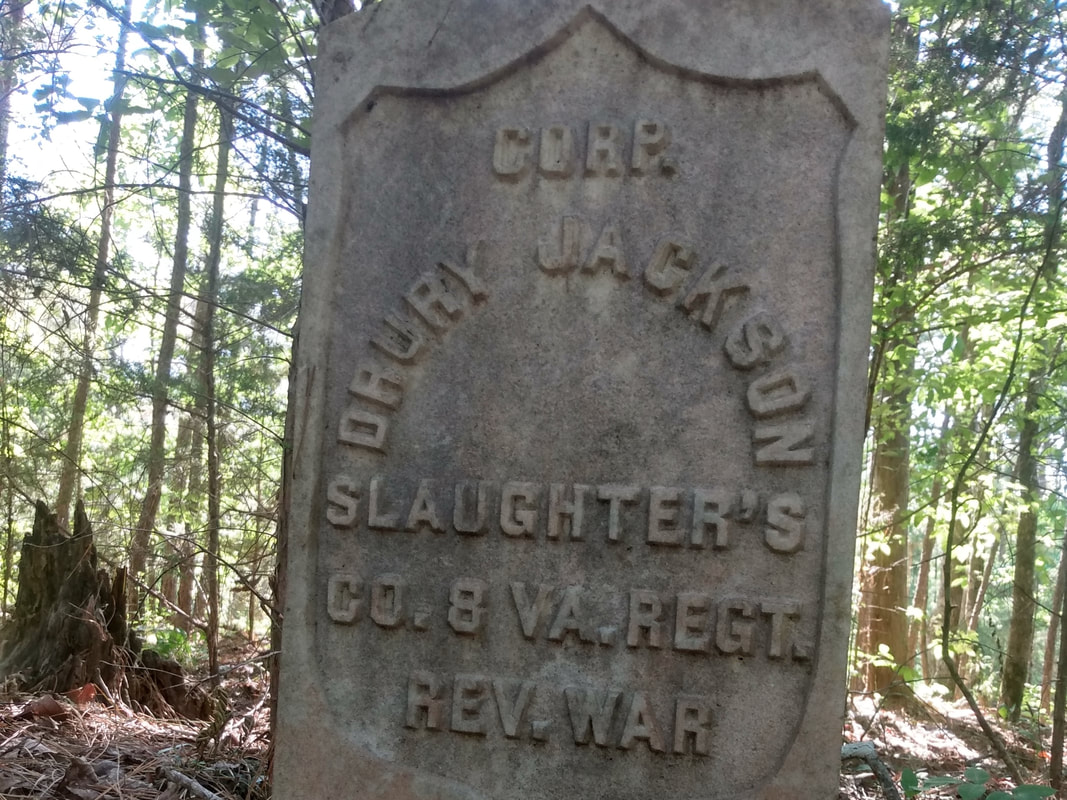

Time changes things. Neither the lake nor the woods were there when Drury Jackson died. Back then the grave was on cleared ground overlooking the Oconee River. Depressions in the soil still reveal to the trained eye that Drury was buried in proper cemetery. The river became a lake in 1953 when it was dammed up to create a 45,000-kilowatt hydroelectric generating station. When Dutch found the grave, the cemetery had been neglected and reclaimed by nature. Today it is in a copse of trees surrounded by vacation homes. Dutch spends his free time studying local history and conducting archeology. He has made some important finds, including a string of frontier forts along what was once the “far” side of the Oconee. He’s pretty sure that Drury’s burial in that spot is an important clue to his life in the years following the Revolutionary War. From there, however, things get complicated. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

0 Comments

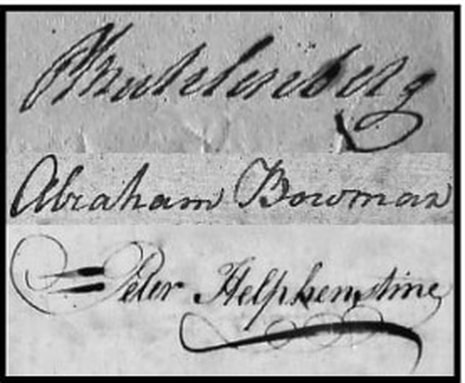

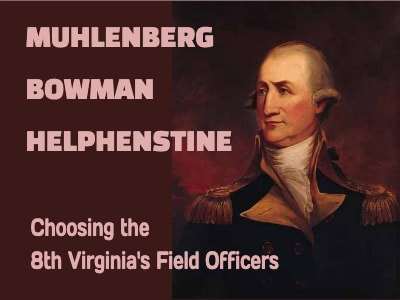

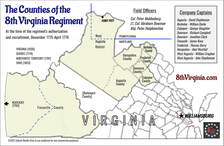

The signatures of Col. Peter Muhlenberg, Lt. Col. Abraham Bowman, and Maj. Peter Helphenstine. (Author) The signatures of Col. Peter Muhlenberg, Lt. Col. Abraham Bowman, and Maj. Peter Helphenstine. (Author) Why Germans? The 8th Virginia Regiment of Foot was authorized by the revolutionary Virginia Convention on December 13, 1775. It had no numeric designation yet, but was intended to be unique in two ways. It would be ethnically-based and all of its men would carry rifles. It was conceived as a “battalion” to “be composed of Germans, with German officers.” The concept may have originated with the Rev. Peter Muhlenberg and Jonathan Clark, both delegates from Dunmore County in the Shenandoah Valley. Dunmore (now called Shenandoah County) was the cultural hub of German life in the Valley. It is inconceivable that the resolution could have been drafted without the involvement of at least Muhlenberg and probably of Clark as well. Muhlenberg was the Rector of Beckford Parish, the geography of which was identical to that of Dunmore County. His church was at Woodstock, the county seat. He was, however, more than just the community’s pastor. He was the son of the patriarch or the Lutheran Church in America, whose church was in the village of Trappe near Philadelphia. Clark was the county’s deputy clerk, an important job, under Thomas Marshall (soon to be colonel of the 3rd Virginia Regiment and father of future Chief Justice John Marshall). The Shenandoah Valley’s Germans had nearly all come the way Muhlenberg had: down the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road to Virginia. The road passed through communities that remain heavily German to this day, such as Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Scotch-Irish immigrants followed the same route, but tended to settle farther south in the Valley, around Staunton and Augusta County. Lutheran Germans like Muhlenberg were seen by the Virginia gentry as reasonably reliable and trustworthy. Their theology differed little from the Church of England. Muhlenberg had, in fact, gone to London to be ordained before taking his position in Woodstock. (King George III was himself of German descent and his great grandfather, George I, couldn’t speak English when he took the throne.) The Ulster Irish, however, were less trusted. They were theological dissenters and often politically radical. Their Calvinist faith differed in important ways from Anglicanism. They could, however, be counted on to fight “And be it farther ordained,” read the resolution, “That of the six regiments to be levied as aforesaid, one of them shall be called a German regiment, to be made up of German and other officers and soldiers, as the committees of the several counties of Augusta, West Augusta, Berkeley, Culpeper, Dunmore, Fincastle, Frederick, and Hampshire (by which committees the several captains and subaltern officers of the said regiment are to be appointed) shall judge expedient.”

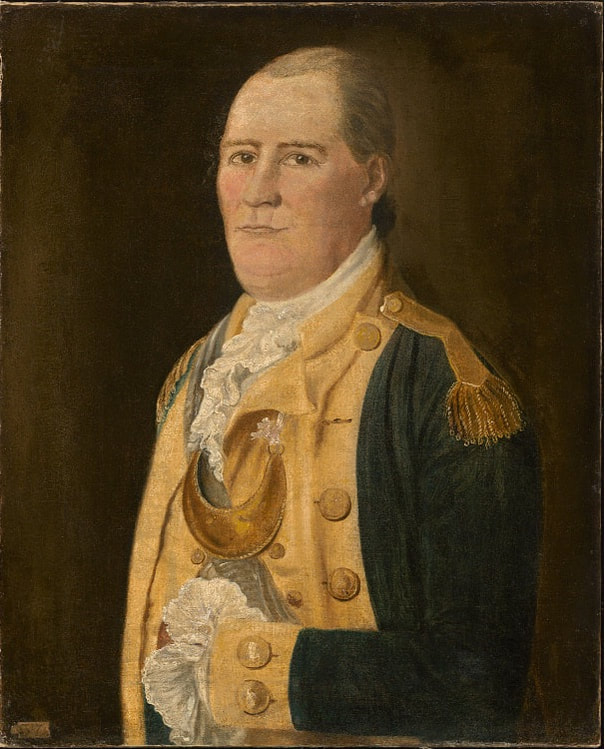

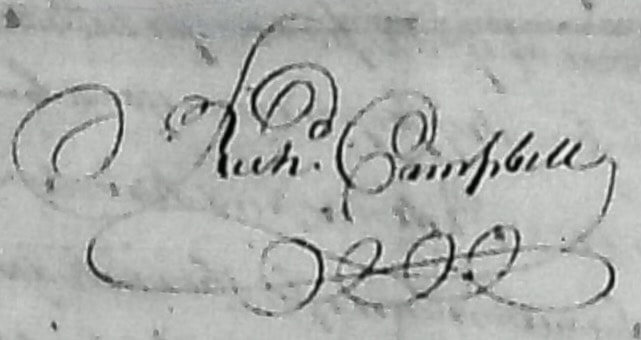

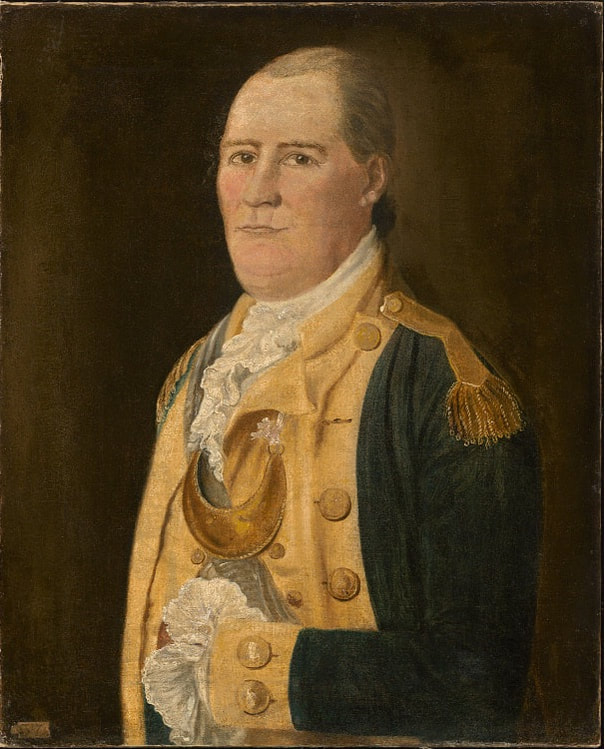

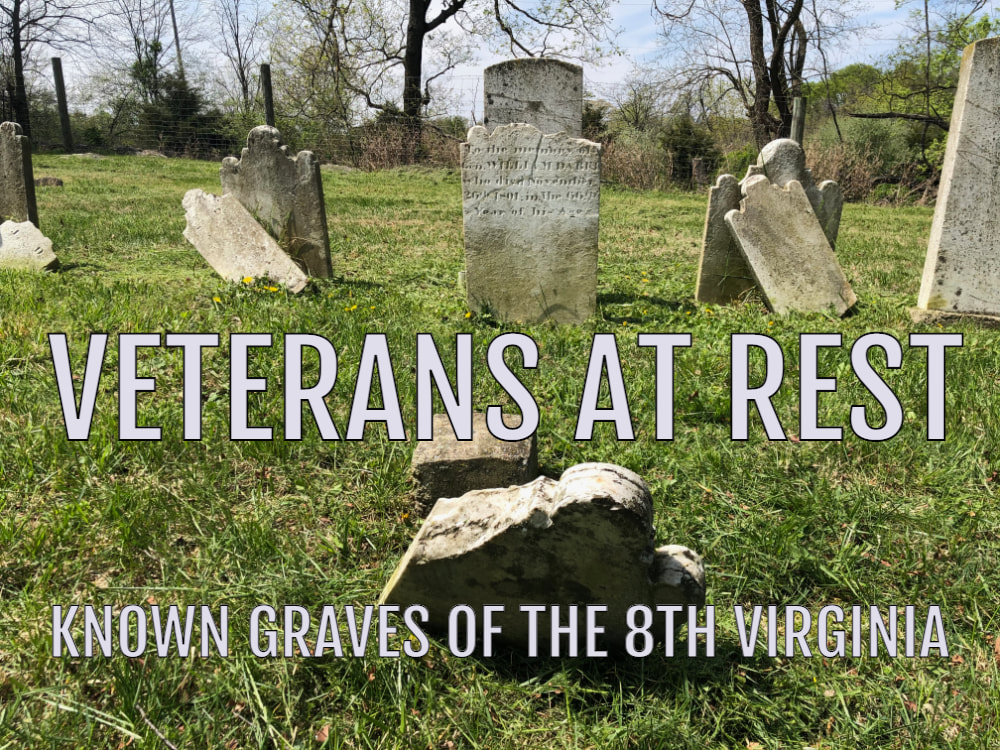

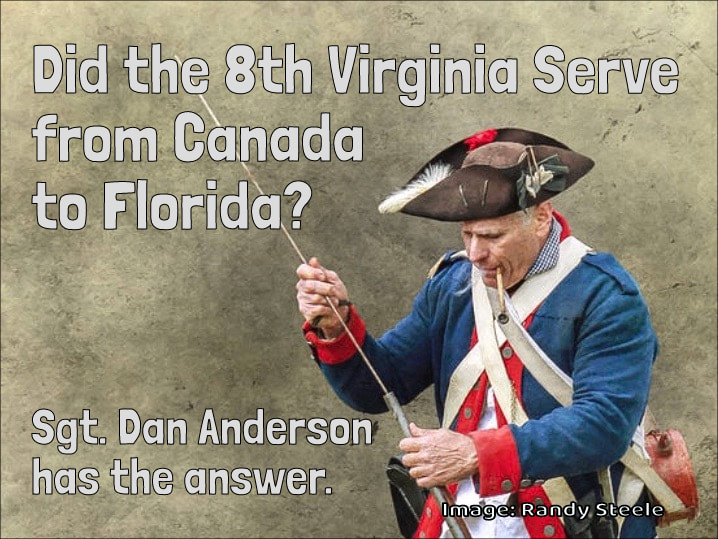

Below them, the officers of the ten companies—captains, lieutenants and ensigns—were a diverse group. English, German, and Scotch-Irish were most common. Capt. Abel Westfall of Hampshire County was Dutch, though his family had been in America for generations. Lieut. Jacob Rinker was Swiss. Lieut. Isaac Israel was Jewish. Religiously, though it is hard to trace, they were mostly Anglican, Lutheran, German Reformed, Presbyterian, and probably Baptist. If there were no Methodists, some of them—including Capt. Westfall—would become Methodists soon. ` The diversity of the officers reflected the diversity in the rank and file. The 8th Virginia was a microcosm of the Continental Army at large. It was America’s original “melting pot.” Originally divided by race and religion, their shared hardships would soon make them a band of brothers. The committees were generally dominated by English elites and could be counted on to appoint the right kind of company officers. Only two of ten companies had Irish captains: Fincastle County and the West Augusta district (both on the frontier) selected James Knox and William Croghan. Both were capable and loyal officers. The choice of field officers, however, was up to the Virginia Convention and it chose three Germans as it had planned. Each was from a different down in the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley. Muhlenberg was appointed to be the colonel. Abraham Bowman of Strasburg (also in Dunmore County) was appointed to be the lieutenant colonel. Bowman came from a prominent family. His grandfather, Jost Hite, had led the first group of German settlers into the valley from Pennsylvania in 1731. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment (Image: Randy Steele) (Image: Randy Steele) As an old man, Daniel Anderson wanted to spend his last years in prayer. He said he would “ever pray for the success and prosperity of his native state and country.” He would pray “to secure the liberties of which in his younger days he voluntarily encountered the perils of war and shed his blood in her service.” These were not platitudes. The bloodshed was real and there is no reason to doubt that his prayers were just as authentic. He was a humbled man. He was disabled by his war wounds and obliged to use the few resources he had caring for his wife and three physically and mentally handicapped adult children. Surprisingly, the unique contours of Anderson’s war service resolve a persistent question. The men of the 8th Virginia fought almost everywhere during the Revolution. I have sometimes described them as having served “from New York to Georgia,” but wished I could say “from Canada to Florida.” The regiment didn't range that far, but I have long suspected that some of its men did over the course of the war. The Florida question remains unsolved. In 1776, Maj. Gen. Charles Lee took the regiment south to attack the Tory haven at St. Augustine. They made it to Sunbury, Georgia before the expedition was called off. The malaria-stick regiment was posted there at Fort Morris, on the Medway River, for some time. Did they ever cross the St. Mary’s River into what was then the colony of East Florida? The governor of Florida reported in October of 1776 that “depredations were made by the Rebels as far [across the border] as Saint John River,” forcing him to commandeer a boat for defense. The main body of the 8th Virginia was probably gone by then, but had any of them gone scouting across the river before the raid? Quite a few men also remained behind to recover from sickness and some--like William Gillihan and Collin Mitchum--transferred to the 5th South Carolina Regiment. Did any 8th Virginia men participate in the foray to the St. John’s River that summer or fall? Probably. Maybe. We may never know.  Daniel Anderson enlisted twice under Daniel Morgan, portrayed here in an anonymous portrait from about 1780. Daniel Anderson enlisted twice under Daniel Morgan, portrayed here in an anonymous portrait from about 1780. The Canada question, on the other hand, is now settled. The very first companies of Congress-authorized “Continental” troops included two companies of riflemen raised in the Shenandoah Valley in July of 1775. I have hoped to find just one 8th Virginia soldier who was in Capt. Daniel Morgan’s Frederick County company. But was there one? Yes. Daniel Anderson enlisted in Morgan’s rifle company in July of 1775 and was with him at Boston and the attack on Quebec. He was wounded at Quebec in the chest and the right arm, captured, and held prisoner for months. He was eventually exchanged and then discharged at Elizabeth, New Jersey. In February 1777 he enlisted again under Morgan, who was now the colonel of the 11th Virginia. There is no record of Anderson in the 11th Virginia rolls, however, because he was promoted to sergeant and transferred into Capt. Thomas Berry’s company of the 8th Virginia. Anderson was with the 8th through Germantown, Whitemarsh, Valley Forge, and Monmouth. He was discharged on February 2, 1779. He then received a state commission as a lieutenant in the Western Battalion of Virginia state troops (state regulars—not militia and not Continentals), probably fighting Indians as far west as Indiana under Col. Joseph Crockett. Other 8th Virginia men were on the frontier as well, serving as far west as Illinois. After the war, Anderson settled in Shenandoah County, Virginia and lived the rest of his life there. So what can we claim for the length and breadth of the regiment’s service? “From Canada to Florida” is still a stretch beyond what we can prove. To the Florida line? Still too far. Until we can prove more, we’ll have to settle for “From Canada nearly to Florida.” Can we also say, “From the Atlantic to the Mississippi?” Not yet, but it’s entirely plausible. Regardless, the range of the 8th Virginia’s men is impressive. Almost all of that movement was covered on foot. In retirement, Daniel Anderson’s wounds kept him from performing hard labor—even the work of a subsistence farmer. Still, he somehow had to support his wife and three disabled children. “I am by occupation a farmer,” he said in 1820, “but owing to wounds and age I am unable to follow it. I have my wife living with me, aged 57 years; 1 daughter, aged 23 years, a cripple; and two dumb children, both simple, one a girl aged 14 the other a boy aged 27. The reason for his older daughter’s disability was her being “so much afflicted with Cancers that she has not been out of the house for 16 months.” The word "dumb" in those days still meant "mute." "Simple" meant intellectually disabled. There were no federal pensions yet, but he applied to the Virginia legislature for pension on the basis of his own service-connected disability. He made his case before a judge. His conclusion was recorded by the court in the third person: “The prayer of your petitioner therefore is that your honorable body will pass an Act allowing such pension as in your wisdom you may deem sufficient to enable him to end his few remaining days in praying, as he will ever pray for the success and prosperity of his native state and country to secure the liberties of which in his younger days he voluntarily encountered the perils of war and shed his blood in her service.” The date of his petition isn’t shown, but it was supported by notes from doctors and a letter from Daniel Morgan in 1796: “The bearer of this Dan’l. Anderson Inlisted a soldier with me in the year 1775 march’d with me to Boston & from thence to Quebec – was with me in the storm of the garison, on the last Day of Dec’r. when Gen;l Montgomery fell. He Rec’d two wounds in the action, one in the Breast & one in his Arm which Doctor senseny & Doctor Balwin certyfies that said wounds has so disabled him as to Rendered unfit for Hard Labour & thinks Him a proper object for a Pension.” "Doctor Balwin" was Cornelius Baldwin, the former surgeon of the 8th Virginia. Anderson received his state pension and later received federal support as well. He died on November 6, 1840. UPDATE: Thanks to Carolyn Brown Butler who alerted us to the pension of her ancestor William Smith. Smith, after his time in the 8th, served under George Rogers Clark and (former 8th VA captain) George Slaughter. He was sent by Clark as an express rider to the Iron Banks, six miles below the mouth of the Ohio on the Mississippi. So now we can say that at least one 8th Virginia man served from "the Atlantic to the Mississippi." More from The 8th Virginia RegimentThere is no dignity in being forgotten. A case in point is Virginia Lt. Col. Richard Campbell, a Continental officer who died bravely for his country but lies today in an unmarked grave far from his home. “Killed near the end of the battle at Eutaw Springs,” wrote the authors of a 2017 study of that battle, “he is virtually unknown today.” In his own day, however, Nathanael Greene called him a “brave, active, and intrepid Soldier.” Light Horse Harry said he was an “excellent officer” who was “highly respected and beloved.” In 1832 one of his soldiers still remembered him as “the brave Col. Campbell.” Dick Campbell, as he was known, deserves to be remembered. Little is known of his early life. Historian Louise Phelps Kellogg asserted a century ago that he was “a distant relative of the Campbell family of southwest Virginia.” This would tie him to militia Gen. William Campbell, a leader at the Battle of King’s Mountain. He was evidently born in Virginia about 1730 and raised in Dunmore (now Shenandoah) County, where he was appointed a sheriff’s deputy in 1772 and reappointed in 1774. The Shenandoah Valley was culturally distinct from the eastern parts of Virginia. Many of Campbell’s neighbors were Germans who had migrated from Pennsylvania.

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment I’ve written twice before about Private William Eagle, who enlisted into the 8th Virginia late in 1777 and joined at Valley Forge just before the two-year enlistments of the original men expired. He was evidently just 16 years old. He was the son of very early settlers of Pendleton County, West Virginia’s remote Smoke Hole Canyon and returned there after the war. He was buried in the beautiful canyon facing a remarkably vertical rock formation that now carries his name: Eagle Rock. Over the years Smoke Hole Canyon became a pocket of Unionism in a region of otherwise intensely pro-Confederate sentiment, a haven for moonshiners, and eventually part of the Monongahela National Forest. His grave, perhaps not permanently marked, was lost for many years until discovered by Forest Service surveyors about 1930 when a new stone was set in the ground. Photos of the spot on the internet show a pretty and bucolic setting. The stone sits under a sycamore tree and appears well-attended with a crisp and clean American flag. Returning recently from a family vacation, however, I stopped by the site and discovered that it looks nothing like those images. In mid-January the stone was half-buried in frozen debris at the end of a virtual river of ice descending from the ridge of North Fork Mountain. The base of the sycamore’s trunk is rotting. It looks as though an impromptu hiking trail has become a path for water runoff. On a 20-degree day following two days of rain, Private Eagle’s grave was covered by forest debris that had washed down the mountain. Attempts to clear it were fruitless. It was frozen solid. Perhaps this is a purely seasonal phenomenon, but a Revolutionary War veteran’s grave deserves better care. It appears to me that thoughtless hikers are the culprits. Someone—the Forest Service, Pendleton County, neighbors, a Boy Scout looking for an Eagle Scout project, the DAR or the SAR—should find a way to protect the grave from what seems like inevitable serious damage.

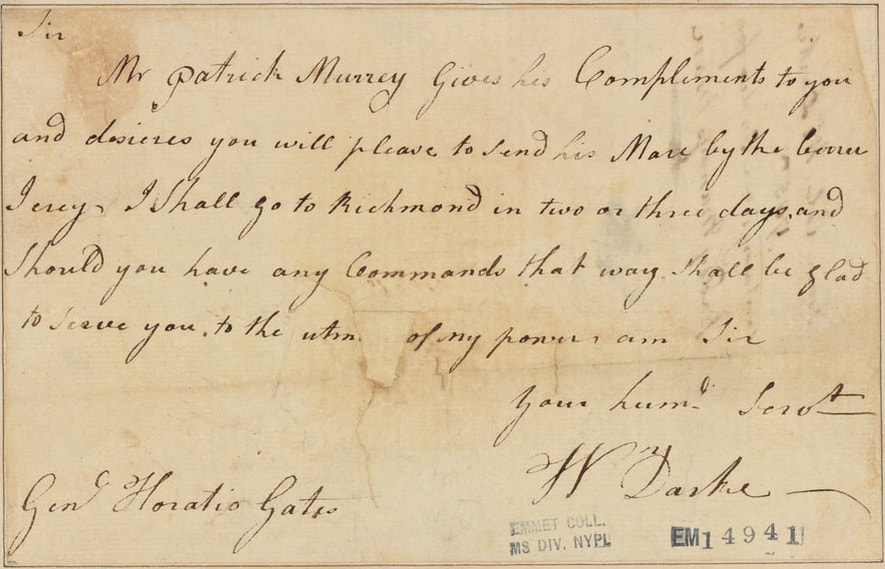

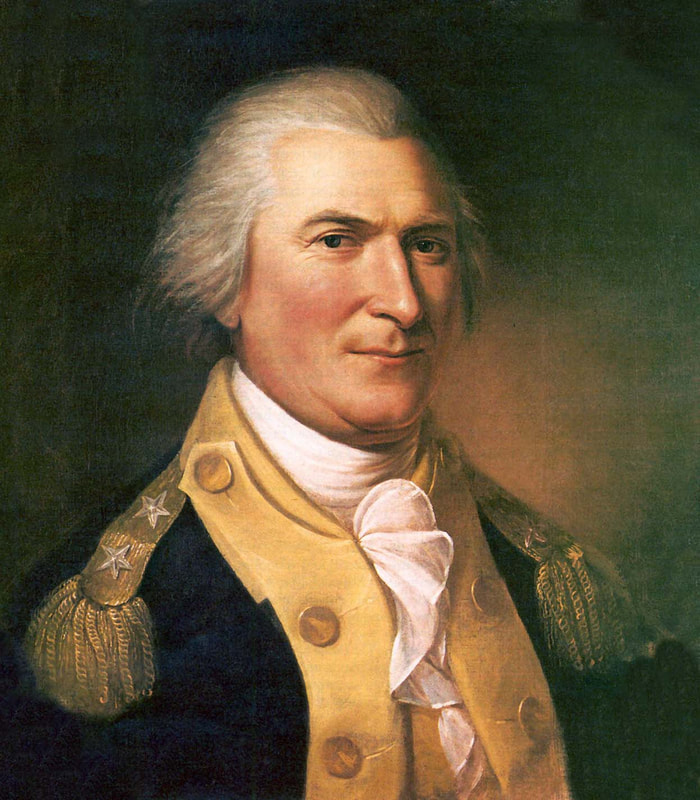

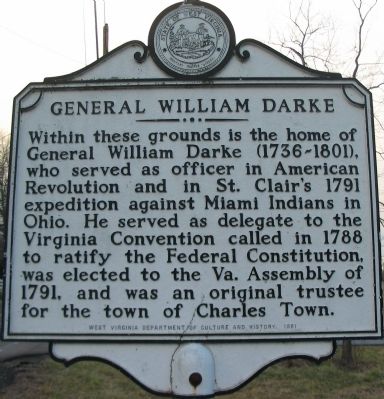

Darke and Washington had much in common. They both grew up in Virginia on the south bank of the Potomac River in Lord Fairfax’s vast proprietary lands. They were both physically large men and belonged to the same generation, born just four years apart. They were both veterans of the French and Indian War and they both committed themselves to the War for Independence in 1775.[2] There was much that separated them as well, including seventy-five miles of river between their homes. Wealth, education, social standing, and military rank all put the colonel below the future president. Their personalities were almost opposite—Darke had that “fire and rashness” while Washington was famously patient and reserved. Washington was refined, while Darke was described as having “unpolished manners.” Nevertheless, war, business, and politics bound them together off and on throughout their adult lives.[3] The French and Indian War They first encountered each other during the French and Indian War. Washington established his military reputation in Major General Edward Braddock’s disastrous expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755. Darke’s earliest biographer dedicated nearly a fifth of his 1835 essay to describing the expedition and its outcome, asserting that in “the nineteenth year of his age” Darke “united himself to the army under the ill-fated Braddock.” The biographer, who is identified only as “a Citizen of Frederick County, Maryland” may have known Darke. A Charlestown Free Press account cited in (and published sometime before) an 1858 Harpers New Monthly Magazine article asserted that Darke “was one of the Rangers of 1755 (then nineteen years old), serving under Washington, in Braddock’s ill-managed march toward Fort Duquesne.” The idea that Darke was with Washington under Braddock has been doubted by some, including Shepherdstown historian Danske Dandridge. She, in 1910, acknowledged the tradition but made a point of saying she had “seen no proof.” Supporting the tradition, however, is Darke’s own statement in a 1791 letter to President Washington that he had “bean in the Service of my Country in allmost all the wars Since the year 1755 in one Capassoty or other.”[4]

Darke’s French and Indian War service evidently concluded in 1759; Washington’s ended the year before. They had both gained valuable military experience. Still in their twenties, they now focused on their domestic lives. Washington married Martha, the widow of Daniel Parke Custis, in January of 1759 and spent the next fifteen years at Mount Vernon. Darke also married a widow, Sarah Deleyea, whose husband had been scalped and killed by Indians while sleeping under an elm tree. Darke and Washington both raised the sons of other men. Unlike the Washingtons, however, the Darkes also had four children of their own. Nothing else is known of Darke’s life in the 1760s other than an unsupported 1888 assertion that he “was engaged in defending the Virginia frontier against the incursions of the savages.”[7] The Revolution The Upper Potomac region responded enthusiastically to the call for troops in 1775. Among the first units to be authorized by Congress was Hugh Stephenson’s company of riflemen from Berkeley County, which competed with Daniel Morgan’s Frederick County company in a race to Boston. Two more companies were raised across the river in Frederick County, Maryland. At the same time Virginia organized two regiments of provincial regulars, some independent companies for the defense of the frontier, and a network of minute battalions. When six more regiments were authorized by the Commonwealth in December, Darke was ready to go with a company of men. It became the first newly-created company of the 8th Virginia Regiment of provincial regulars and he was commissioned to be its captain.[8]

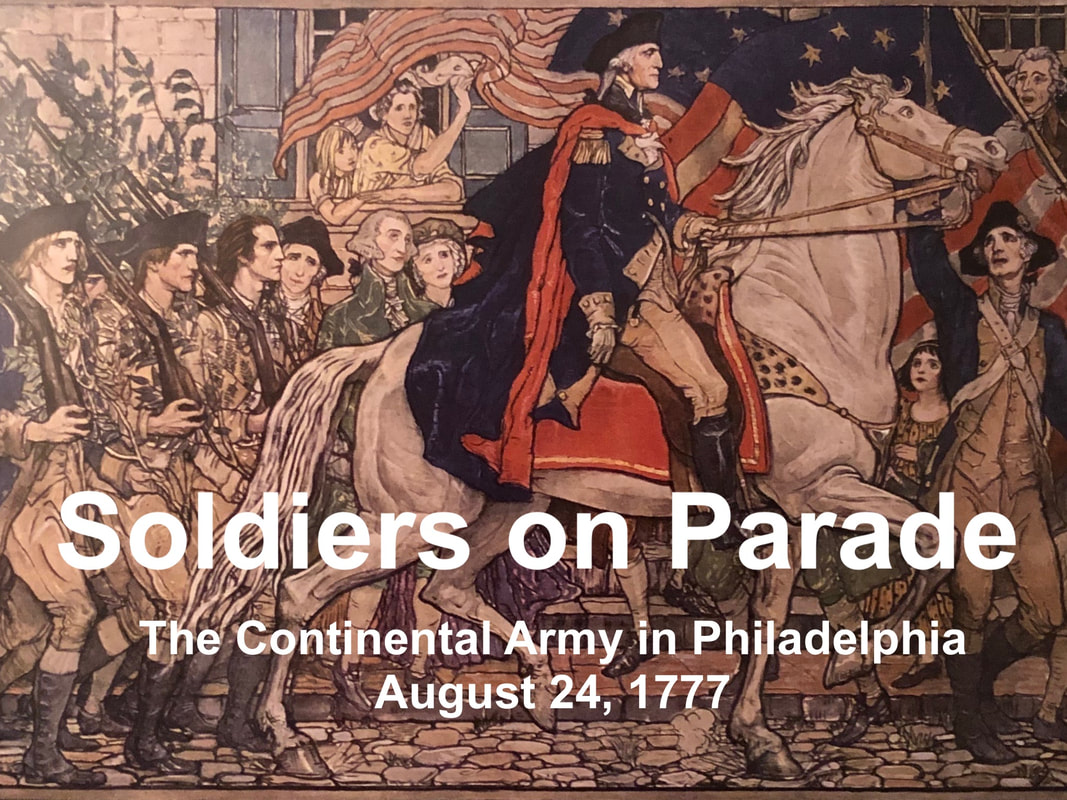

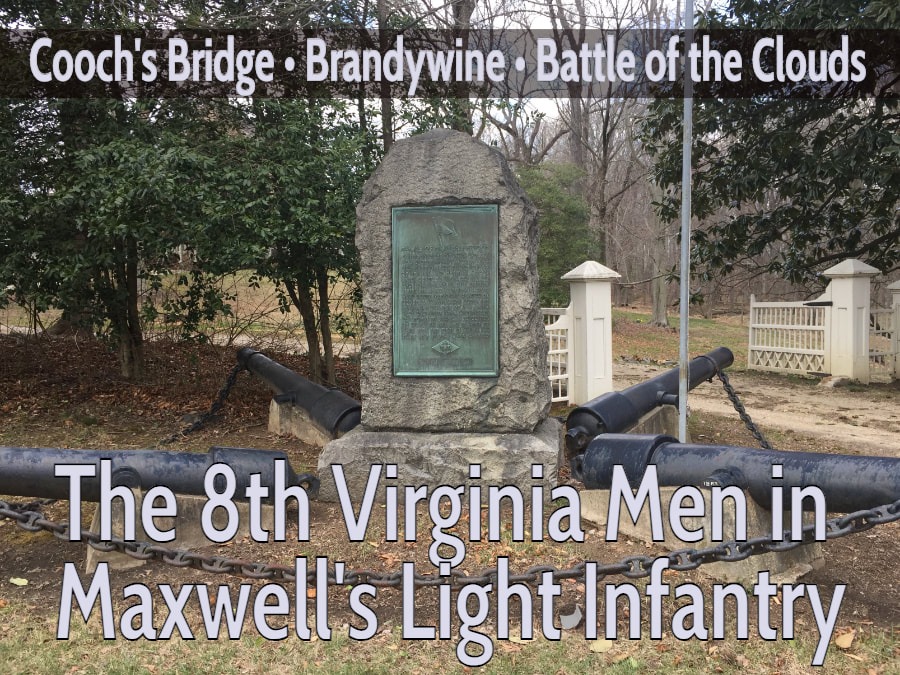

The regiment’s rendezvous point was Suffolk, a choke point in Virginia’s terrain between Williamsburg and Tory-dominated Norfolk. In the spring of 1776, they kept watch over Tories and stopped slaves from joining Governor Dunmore’s army of Loyalists. After the arrival of Major General Charles Lee, commander of the Southern Department, they marched south to protect Charleston, South Carolina. Darke’s men were present for (but probably not directly engaged in) the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on June 28. Other 8th Virginia men helped fend off an enemy landing on the north end of the island but they were not involved in the famous defense of Fort Moultrie at the island’s southern end. After they fended off the British a greater danger appeared: malaria. Most of Muhlenberg’s men had no resistance to it. As he headed farther south to attack Florida, Lee left a large group of sick men behind in Charleston. The advance never made it past Sunbury, Georgia. According to an 1802 account, “The troops that went to Georgia, suffered exceedingly by sickness; at Sunberry, 14 or 15 were buried every day, till they were sent to the sea Islands, where they recruited a little.” Darke lost nearly half his company to the disease.[9] Among the first to get sick was 8th Virginia major Peter Helphinstine, who returned home to Winchester and died. On the day the army marched south from Charleston, Lee appointed Captain Richard Campbell to replace Helphinstine. In doing so, he passed over Darke, who was the senior eligible captain. No reason is given in the record, but the best explanation is that Darke was sick, left behind, and perhaps not expected to recover. Congress confirmed Campbell’s new rank.[10] The promotion became a source of controversy when the regiment returned to Virginia and Campbell began to oversee recruitment for the 1777 campaign. Unable to address the matter himself, Muhlenberg appealed to Washington for help. An aide de camp responded to him, writing, “Congress having confirmed Majr Campbell in his Office, leaves his Excellency no power to remove him, but for the Commission of some Offence.”[11] Controversies related to rank and promotion were common in the Continental Army. Muhlenberg himself was made a brigadier general at this time, which caused problems of its own. Darke’s case was handled delicately. On May 13, Congress gave Washington the authority to look into Darke’s case and resolve it. Explicitly authorized to make the decision, Washington promoted Darke to major. For purposes of seniority, the promotion was made retroactive to January 4, but its effective date was delayed until the end of September. This was evidently Washington’s way of looking out for a trusted soldier and compensating Darke for an injustice. Major Campbell kept his rank but was transferred to another regiment.[12] While the controversy was sorted out, Darke was put on detached duty, sometimes performing jobs that might have been assigned to a major. In June, Washington put Darke in command of 150 Virginia riflemen alongside General Anthony Wayne and Colonel Daniel Morgan. They harassed the enemy as Howe withdrew from New Jersey and they were centrally engaged in the Battle of Short Hills.[13] When Howe’s army sailed away, Washington sent Morgan’s Rifles, an elite unit, north to join the forces under Major General Horatio Gates opposing British General John Burgoyne. Howe, however, was headed in the opposite direction. When that was discovered, Washington rushed his army south and on August 28 ordered his brigades to each supply 117 of their most capable men to form a new light infantry force under the command of New Jersey’s General William Maxwell. Specifically, each brigade was to provide“one Field Officer, two Captains, six Subalterns, eight Serjeants and 100 Rank & File.” William Darke was chosen for this service by General Charles Scott, his brigade commander, possibly at Washington’s direction. Maxwell’s Light Infantry was the sole Continental unit at the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge and played an important role on both sides of the river at Brandywine a week later.[14]

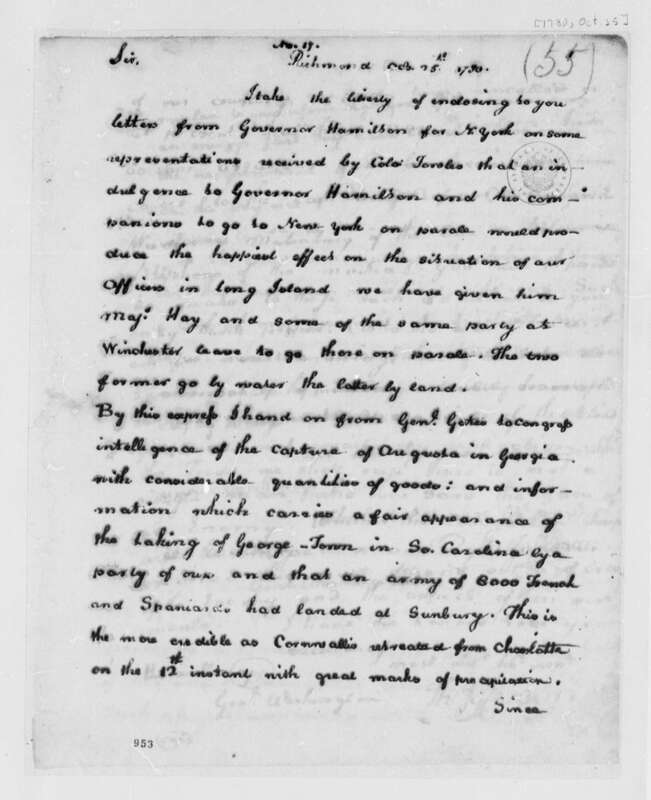

In May of 1780, Darke and other captive officers wrote to Governor Thomas Jefferson asking for financial support. The only thing of real value Virginia could offer them was tobacco, which the prisoners could barter with or sell. Jefferson wrote to Washington, who was encamped near New York, advising him that the Virginia legislature had authorized a shipment of tobacco for the prisoners and asked him to see if the British would allow it. If not, the tobacco was to be sold for hard money, which would then be sent to the men. Washington advised that the latter course would have to be followed. [17] The general and the governor were both interested in getting Darke and his comrades home, perhaps on parole (honor bound not to fight) or properly exchanged (free to take up arms again). Jefferson had the necessary leverage. In February, 1779 Virginia state troops had captured Henry Hamilton, the lieutenant governor of Quebec and the Crown’s superintendent of Indian affairs. Based at Fort Detroit, Hamilton had been in command of British military efforts in the northwest and was hated by Virginia frontiersmen. On October 25, 1780 Jefferson played this valuable card. Hamilton and a few other British prisoners were traded for several American officers on Long Island. At last, Darke was free. Washington wrote to Congress that a total of fifteen American officers were on their way home. “The Military Chest being totally exhausted,” he wrote, “they will with difficulty be enabled to get as far as Philada. I must solicit you to procure them a supply there, sufficient to carry them home. Their long and patient sufferings entitle them to attention and to every assistance in getting themselves and Baggage forward.”[18]

Things escalated significantly in May when Lord Charles Cornwallis invaded Virginia and occupied Richmond with a large army. The Virginia legislature fled to Charlottesville, but was pursued by Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarlton’s dragoons. The alarmed legislature appealed to the recently-promoted General Daniel Morgan for help. The hero of the Battle of Cowpens (January 17, 1781) had returned home to Winchester suffering from sciatica and other ailments. Governor Jefferson wrote to him on June 2, urging him to raise an army in the Shenandoah Valley and come to the commonwealth’s rescue. Morgan agreed, but found men reticent to leave home as the harvest season approached. This led him to “call on the best aid I could possibly get” in convening a group of “Gentlemen who I esteem of most influence.” This group met on June 15 to plan and prepare. Among them were General Gates, Lieutenant Colonel Darke, and a handful of other prominent military men from Frederick and Berkeley counties. [20] They set about recruiting men to defend the Commonwealth, urging the legislature to “provide some decisive measure for procuring the number necessary.” Properly equipping the recruits also proved challenging. At last, Morgan and Darke arrived with reinforcements on July 7, the day after the Battle of Green Spring. Morgan’s health, however, soon forced him to return home again. For the time being, the Americans remained in camp near Williamsburg while Cornwallis established a base at Yorktown. Meanwhile, the French persuaded Washington that there was an opportunity in Virginia, and they proceeded south with the main army from New York.[21] Washington arrived in Williamsburg on September 14. The troops formed up so he could review them. Many or most of these soldiers had never seen the great general before. The following day the officers lined up to greet Washington at a reception. It may have been at this event that Darke inappropriately “made the first motion” to the commander-in-chief. It was George Bedinger, one of Darke’s captains, who wrote, “I have never been able to account for such a motion. I suppose it was the Colonel’s usual fire and rashness, and, that Washington perhaps had a desire to know what the enemy would do on such an occasion. It was in my opinion an extraordinary and, I think unnecessary temerity.” Darke may simply have been eager to express his gratitude for his freedom.[22]

Business and Politics After the war, Colonel Darke focused on his home and his family. He and his wife raised their own four children, an older son from Sarah’s first marriage, and a local orphan. In addition to whatever farming he engaged in, Darke made forays into both business and politics. He was now a man of stature in his community.[24] He became deeply involved in America’s first interstate public works project, working closely with (and for) Washington. As the Kentucky country filled up with settlers, it became apparent that there were economic, political, and strategic imperatives for connecting the Ohio watershed with the east. For Kentuckians, it was significantly easier to transport goods down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to Spanish New Orleans than it was to transport them upstream and overland to ports on the Atlantic coast. To counteract this, there was intense interest in creating a junction between the Ohio and Potomac Rivers via the Monongahela and Youghiogheny rivers. Success would keep Kentucky tied to the United States and keep the value of its produce headed east.[25]

In 1789, the river was sufficiently clear for Darke to make news in Richmond’s Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser. We cannot but congratulate our readers on the fair prospect of Patowmack, becoming soon the common channel of conveyance for the produce of the fertile country through which it runs. The water carriage is already so far established, that five wagons are kept constantly plying between waters’s branch, the common landing, of George-Town. Colonel Darlk’s boat last week, brought down a load of 262 barrels of flour from Shepherds-Town, in Virginia, and passed Shanandoah and Seneca Falls, with safety and ease.[27] Ultimately, the project was unsuccessful. Dry weather left the river impassible while too much rain flooded the bypass “canals.” The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was later built to replace it (on the other side of the river). Even that canal never connected the Potomac and Ohio rivers.[28] Washington’s other great project during this period was the drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution. The proposal was controversial in Virginia, with leading figures like Patrick Henry and George Mason opposed to it. A convention was called to ratify (or reject) the document and Darke was elected to be one of two delegates from Berkeley County. His partner was retired Major General Adam Stephen, who had ordered Darke into the fog at Germantown. Both of them supported the Constitution, prevailing in an 89 to 79 vote.[29]

After taking office, President Washington signed legislation authorizing the location of a new capital city on the Potomac River “at some place between the mouths of the Eastern-Branch and Conogocheague.” In other words: somewhere between Georgetown (then in Maryland) and Williamsport (still in Maryland), an 85-mile stretch of river. In October of 1790, Washington visited Shepherdstown and met with Darke and other locals to discuss the possibility of locating the capital at Sharpsburg—just across the river. He also visited Hagerstown and Williamsport, but ultimately selected the Georgetown location.[31] War with the Indians In 1791, Darke was elected to the Virginia General Assembly. His time in that office was short, however, because Washington had other plans for him. Rapid settlement of Kentucky had enraged Indians in Ohio who used Kentucky as their hunting grounds. By one account, as many as 1,500 settlers were killed over a period of just a few years. A campaign against the Indians in 1790, led by Brigadier General Josiah Harmar, had been a failure. An earlier campaign under Colonel William Crawford had resulted only in the colonel’s capture, brutal torture, and execution. Shortly after Darke’s election, he received a letter from President Washington asking him to lead a regiment of “levies” in a major new campaign. Levies were federal soldiers on short-term (six month) enlistments. Washington asked Darke to “appoint from among the Gentlemen that are known to you, and who you would recommend as proper characters, and think likely to recruit their men, three persons as Captains, three as Lieutenants, and three as Ensigns in the Battalion of levies to be raised in the State of Virginia, for the service of the United States.”[32]

The advance looked much like General Braddock’s march of 1755, and concluded much the same way. They cut a road through the wilderness as they went, needing it to run a supply train. Insufficient supplies, poor morale, expiring enlistments, bad weather and bickering officers all contributed to a horrific defeat on November 4. Surrounded, General St. Clair’s army—camp followers included—was sniped at and then butchered to pieces by the Indians as men fled in panic back down the road. Their flight was made possible by a desperate charge through the Indian lines led by Colonel Darke. General Butler and Darke’s son were both among the hundreds of dead who made up the largest loss for any U.S. Army in any war before the Battle of Shiloh in 1862.[34] Though painfully wounded in the leg, Darke was the only senior officer to survive the massacre with both his life and his reputation intact. This was in part because of his conduct and in part because he sent his own report on the battle to the President in a letter he made sure was public. This enabled him to influence public perception of the disaster before any investigations or recriminations began. In his letter to Washington Darke was critical of General St. Clair but placed the greatest blame on Major John Hamtramck of the 1st U.S. Regiment, whom he openly accused of cowardice. Two months later, on his way home, he sent a blistering criticism of St. Clair to a member of Congress who leaked the letter to the press.[35] Darke wasn’t just playing the blame game. He was angry and he was grieving. His son, Joseph, died “after twenty-seven days of unparalleled suffering.” Another of Darke’s three sons, John, died shortly after the colonel returned home from the battle. John’s death was probably a coincidence, but at least one historian seems to have interpreted it as another battle casualty. Darke’s old French & Indian War commander, Robert Rutherford, reported the second death to President Washington in March. “I Indeed sympathize Very tenderly with him on the death of his sons,” he wrote, “as that of his youngest was followed by the death of his eldest son, a few days after his return home and who left a small family.”[36] St. Clair’s terrible defeat was the subject of the first Congressional oversight investigation. Darke left home for Philadelphia in mid-March and testified against St. Clair. The general was exonerated, but his reputation never fully recovered. Darke also visited the president during this trip and had a private conversation with him about the next campaign. Washington asked Darke for his views on who should command. Darke recommended Daniel Morgan, Charles Scott, and Henry Lee—all Virginians. Darke did not realize, and Washington did not say, that for political reasons the commander could not be a Virginian. Lee, known as “Light Horse Harry” from his service in the Revolution, was well regarded but had only been a lieutenant colonel in the Revolution. Washington said he was concerned that officers, including Darke, who had outranked Lee would refuse to serve under him. Washington pressed Darke on the question. Darke does not seem to have given a clear answer, which apparently confirmed the president’s view. Washington, however, told Darke that he had a high opinion of Lee, and Darke left with the impression that Lee was going to get the job.[37] Darke then spoke separately with Secretary of War Henry Knox, who was less guarded and told Darke that Lee would not get the job. Darke thought he knew otherwise and that Knox was wrong. Darke later admitted to Lee that he didn’t give a clear answer to Washington about the rank issue. “I did not answer though I Confess I think I Should,” he wrote in a letter. He blamed it on “being so distressed in mind for Reasons that I need not Mention to you,” but said he “Intended to do it before I left town.” Instead, on his way home from Philadelphia, Darke wrote to the President, saying, “I wanted much to have seen you before I left the City but judging you were much ingaged in business of grate importance, did not wish to intrude. I wanted to know who would Command the army the insuing Campaign and I am informed Genl St. Clear has resigned…. Should you think me worthy of an appointment in the army I should want to know who I was to be Commanded by.”[38] Washington chose General Anthony Wayne, of Pennsylvania. Wayne was a controversial choice, especially in Virginia, and Darke was surprised. He said so to Lee, telling him that Washington had expressed a high opinion of him. He also noted that Knox had indicated Lee would not get the job. Lee took that to mean that Knox had undercut him, and complained to the President in a letter that Knox had “exerted himself to encrease certain difficultys which obstructed the execution of” Washington’s wishes.[39] Read together, the letters can be interpreted to indicate compounding misunderstandings and perhaps an overreaction on Lee’s part. Nevertheless, Washington was clearly annoyed with Darke. He told Lee that it was all nonsense and “declared” that “the conduct of Colo. D___ is uncandid, and that his letter is equivocal.” Wayne went on to achieve a major victory against the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Darke was not asked to serve.[40] The Whiskey Rebellion He did, however, get a chance to serve under Henry Lee. While Wayne’s campaign was the largest military enterprise of 1794, it was not the only one. Darke and Washington were both more directly involved in another: the Whiskey Rebellion. A new federal excise tax on distilled spirits was seen as unfair by western farmers, who found whiskey far easier to transport and sell to eastern markets than raw grain or flour. When the Whiskey Rebellion grew out of control, Washington ordered a military operation to suppress it.

The entire Virginia force was under the command of the man Darke had recommended to Washington. Henry Lee was now the Governor of Virginia and decided to personally lead the Commonwealth’s forces. Lee estimated in a letter that the Pittsburgh tax protestors had about 16,000 men in arms, but predicted, “The division of sentiment among them will greatly diminish this force, and 8 or 9,000 will probably be the ultimate point they can reach. They abound in rifles, and are good woodsmen. Every consideration manifest the propriety of hurrying the march of the troops….”[42] Morgan ordered his men to rendezvous at Winchester on September 15. Darke and his men arrived on time, but “having neither arms, ammunition, or any kind of military stores” General Morgan thought it best to furlough them for a week. Finally, on October 6, another officer reported, “The State Arsenal has furnished us with 3,000 stand” of arms. “This supply enabled us to forward 2,000 men completely equipped on Saturday last. They marched under the command of General Dark. General Morgan follows to-day.”[43] President Washington personally led the advance of other troops from Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Darke and the southern troops rendezvoused with Washington at Cumberland, Maryland, and were reviewed there by the president. Washington then returned to Philadelphia, but left a letter commending the soldiers for their “patriotic zeal for the Constitution and Laws” of the nation. “No citizen of the United States can ever be engaged in a service more important to their country,” he wrote. “It is nothing less than to consolidate and preserve the blessings of that Revolution, which at much expense of Blood and Treasure constituted us a free and independent nation. It is to give to the world an illustrious example of the utmost consequence of the cause of mankind.”[44] Washington was very concerned about maintaining the moral high ground, seeking only to quell the uprising and enforce the tax law. He warned about acts of extrajudicial “justice” against the whiskey rebels. Daniel Morgan personally intervened to prevent such acts. Moreover, William Findley recalled that Morgan’s left wing (Darke’s men included) behaved better than the right wing of Pennsylvania and New Jersey troops. Findley wrote: In one or two instances, where there was danger of some foolish men who mixed with that wing being skewered, general Morgan, by pretending to reserve them for ignominious punishment, saved them, till they could be safely dismissed, or kept his men from killing them by threatening to kill them himself.[45] No accounts of General Darke’s conduct during the operation have been found, but the record shows that the men under Morgan restrained themselves. Findley noted that, “There was not so much of the inflammatory spirit observable in the left wing of the army as in the other, nor was there any persons killed by them, by accident or otherwise.”[46]  Darke, as a militia brigadier general, led Virginia troops in suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Darke, as a militia brigadier general, led Virginia troops in suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Before the army left, a separate corps was formed to encamp near Pittsburgh and “cause the laws to be duly executed.” It was a combination of men from the expedition force and of locals, some of whom “were said to have been the most troublesome of the insurgents.” It is not known if Darke was part of this force, which remained behind for another three months.[47] Nor is it known whether Darke and Washington spoke to each other at Cumberland when the President reviewed the troops there. Some contact seems almost certain given their relationship and Darke’s new rank as a general. Either way, it was probably the last time they encountered each other. The Indian war in the Northwest Territory was over and Washington was half way through his second and final term as President. Five years after the rebellion was put down the Father of the Country was dead. Two years after that, in 1801, Darke was dead as well. His last public office was an appointment to the court (government) of the newly-formed Jefferson County. The court met for the first time just two weeks before Darke died.[48] Conclusion On January 19, 1800, Henry Holcombe—a Revolutionary War officer turned Baptist preacher—delivered a prominent sermon on the life of Washington. He observed that Washington’s greatness was rooted in his freedom from pride and his trust in God. He said Washington’s “boldness and magnanimity, could be equaled by nothing but his modesty and humility.” Moreover, “he displayed an equanimity through the most trying extremes of fortune, which does the highest honor to the human character. He was the same whether struggling to keep the fragments of a naked army together in the dismal depths of winter, against a greatly superior foe, or presiding under the laurel wreath over four millions of free men!”[49]

[1]Danske Dandridge, Historic Shepherdstown (Charlottesville: The Michie Company, 1910), 261. [2]Peter Force, ed., American Archives, (Washington: M. St. Clair Clark and Peter Force, 1837), 4th Ser., Vol. VI, p. 1556. [3]“From John Hurt,” January 1, 1792, The Papers of George Washington, W.W. Abbott, et al., eds. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987-),Presidential Series, 9:358-366. [4]“Biographical Sketch of Gen. William Darke of Virginia by a Citizen of Frederick County, Maryland” in The Military and Naval Magazine of the United States, 6 (1835): 1-9; Dandridge, Historic Shepherdstown, 256; William Darke to George Washington, July 25, 1791, Jefferson County Museum manuscript collection, Charles Town, West Virginia; “Memoirs of Generals Lee, Gates, Stephen, and Darke,” HarpersNew Monthly Magazine,17 (1858): 509-510. [5]David Preston, Braddock’s Defeat (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 180-182, 338-340; René Chartrand, Monongahela 1754-1755: Washington’s Defeat, Braddock’s Disaster (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2004), 56-57; Samuel Kercheval, A History of the Valley of Virginia (Winchester: Samuel H. Davis, 1833, repr. Heritage Books, 2001), 67; Robert Rutherford affidavit, Berkeley County Land Bounty Certificate, 1780, cited in William Armstrong Crozier, Virginia County Records(Baltimore: Southern Book Company, 1904; reprinted as Virginia Colonial Militia: 1651-1776, Genealogical Publishing, 2000), 2:44; “From Robert Rutherford,” March 13 1792,” Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:97-100. [6] “To Robert Rutherford,” June 24, 1758, Papers of Washington, Colonial Series, 5:239. [7]Kercheval, History of the Valley of Virginia, 86-87;Virgil A. Lewis, “General William Darke, A Distinguished West Virginia Pioneer,” reprinted in F. Vernon Aler, Aler’s History of Martinsburg and Berkeley County, West Virginia (Hagerstown, Md.: Mail Publishing, 1888), 193-199. [8]Robert K. Wright, Jr., The Continental Army (Washington: Center for Military History, 1986), 24-25; William Walter Hening, The Statutes At Large, Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature in 1619 (Richmond: J. and G. Cochran, 1821) 9:16-25, 78, 80; Force, American Archives, Ser. 4, 6:1556; Guide to Military Organizations, 43. On June 8, the Virginia Convention heard a claim for expenses incurred by Darke and by Isaac Beall “for the expenses incurred in supporting their two Companies of Riflemen from the time of their being imbodied till the passing of the Ordinance directing the same to be raised.” Darke’s company was junior in seniority by John Stephenson’s company, which was transferred from independent service into the regiment. [9]Jonathan Clark, Diary,June 24, 1776, Filson Historical Society manuscript collection, Louisville, Ky.; Charles Lee to John Armstrong, July 14, 1776, in The Lee Papers,Henry Edward Bunbury, ed., 4 vols. (New York: New York Historical Society, 1871-1875), 2:139-140; William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, So Far as it Related to the States of North and South Carolina, and Georgia, 2 vols.(New York: David Longworth, 1802), 1:186; George M. Bedinger, The George Bedinger Papers: Volume 1A of the Draper Manuscript Collection, transc. Craig L. Heath (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2002), 68; John Robert McNeill, Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 203,229. Lee had other regiments under his command, so the deaths of 14 or 15 men a day does not reflect mortality rates in the 8thVirginia alone. [10]Peter Muhlenberg to James Wood, September 29, 1801 and Peter Muhlenberg affidavit, December 10, 1802, both in Peter Helphinston file, Revolutionary Bounty Warrants, Library of Virginia; Journals of the Continental Congress, 7:52. Captain John Stephenson was senior to Darke, but his company’s term ended in the fall of 1776 and he left the regiment. [11]George Johnston to Peter Muhlenberg, March 9, 1777, Papers of Washington,Revolutionary War Series, 8:429. [12]“To Brigadier General William Woodford,” March 3, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 8:507-508; JCC,7:351-352; John Fitzgerald to Richard Campbell, August 4, 1777, George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, Series 3b, Varick Transcripts, Letterbook 4:13; “To John Hancock,”May 16, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 9:438-439; Washington, General Orders, September 29, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 11:343; Compiled Services Records of American Soldiers Who Served in the Continental Army During the Revolutionary War, 1042:116, 118-119, 134, 146. [13]“Narrative of Sergeant William Grant,” in John Romeyn Brodhead, ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York Procured in Holland, England, and France, (Albany: Weed, Parsons and Co., 1857), 8: 728-734; Clark, Diary,June 22-24; “To Major General Israel Putnam,”August 16, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 10:642; McGuire, Philadelphia Campaign, 1:45-52. [14]“General Orders,” August 28, 1777, Papers of Washington,Revolutionary War Series, 11:81-82; “Narrative of William Grant,” 733. Grant describes how, in a skirmish, Darke “divided his men into 6 parties of 25 each.” [15]“From Major General Adam Stephen,” October 9, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 11:468–470. [16]Elizabeth Paschal O’Connor (Mrs. T.P. O’Connor), My Beloved South(New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1913), 100-101; CSR, 1042:120, 121, 129, 133. [17]“Memorial of the Officers of the Virginia Line in Captivity,” May 24, 1780, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 3: 388-391; “To Benjamin Harrison,” June 22?, 1780, Papers of Jefferson, 3:458; “To George Washington,” July 4, 1780, Papers of Jefferson,3:481; “To Governor Thomas Jefferson,” August 29, 1780, John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1937), 19:468. [18]“To George Washington,” October 25, 1780, Papers of Jefferson, 4:68; “To the Board of War,” November 4, 1780, Writings of Washington, 20:291-292. [19]Michael Cecere, The Invasion of Virginia 1781 (Yardley, Pa: Westholme, 2017), 8-10, 13-14, 22-23. [20]“To Daniel Morgan,” June 2, 1781, Papers of Jefferson, 6:70-71; William P. Palmer, ed., Calendar of Virginia State Papers (Richmond: Sherwin McRae, 1881), 2:162-163. [21]Don Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 161-166, citing Morgan to Nelson, June 26, 1781, Charles Roberts Autograph Collection, Haverford College Library. [22]Ebenezer Denny, Military Journal of Major Ebenezer Denny (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1859), 38-39; James Carter pension, 1833, C. Leon Harris, transc., revwarapps.com (viewed 12/17/17); Dandridge, Historic Shepherdstown,261. [23]James Carter pension, 1833; Dandridge,Historic Shepherdstown, 260-261 [24]Oliver Evans, The Young Mill-Wright and Miller’s Guide (Philadelphia: Oliver Evans, 1795), 500-507. [25]Sarah Peter, Private Memoir of Thomas Worthington, Esq. of Adena, Ross County, Ohio (Cincinatti: Robert Clarke & Co., 1882), 4, 9-10; Douglas R. Littlefield, “The Potomac Company: A Misadventure in Financing an Early American Internal Improvement Project,” The Business History Review, 58 (1984): 562-585. An Ohio-Potomac junction would certainly have required an overland portage as well, but the sources consulted don’t mention one. [26]Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds, The Diaries of George Washington (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia: 1979), 5:6,151-152; “From Henry Bedinger and William Good,” Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, 7:1. [27]Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser, May 14, 1789. [28]Littlefield, “The Potomac Company,” 576, 583-584. [29]Hugh Blair Grigsby, The History of the Virginia Federal Convention of 1788 (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 1891), 2:363-366; Earl G. Swem and John W. Williams, A Register of the General Assembly of Virginia, 1776-1918 and of the Constitutional Conventions (Richmond: Davis Bottom, 1918), 34, 36, 243, 366. [30]Erik Goldstein, Stuart C. Mowbray, and Brian Hendelson, The Swords of George Washington (Woonsocket, RI: Mowbray Publishing, 2016), 63-68; Merrill Lindsay, “A Review of All the Known Surviving Swords of Gen. George Washington: How Many Swords Did George Washington Wear at His Inauguration?” American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin, 32 (Fall, 1975), 37-49. [31]https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Residence_Act_of_1790.jpg; Kenneth R. Bowling, The Creation of Washington D.C: The Idea and Location of the American Capital (Fairfax, VA: George Mason University Press, 1991), 123-125, 210-211. [32]Earl G. Swem and John W. Williams, A Register of the General Assembly of Virginia, 1776-1918 and of the Constitutional Conventions (Richmond: Davis Bottom, 1918), 34, 36, 243, 366; “To William Darke,” April 4, 1791, The Papers of George Washington,Presidential Series, 8:55-57. Darke’s appointment was made after two higher-profile officers declined the job. [33]John Winkler, Wabash 1791(Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2011),21, 29. [34]Wilson, “St. Clair’s Defeat,” 379; Winkler, Wabash,59-73; “Shiloh,” American Battlefield Protection Program, https://www.nps.gov/abpp/battles/tn003.htm(accessed 7/27/18). [35]Dandridge, Historic Shepherdstown,261; “From William Darke,”November9-10,1791,” Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 9:158-168; Arthur St. Clair, Narrative of the Manner in Which the Campaign Against the Indians in the Year One Thousand Seven Hundren and Ninety-One, Was Conducted, Under the Command of Major General Arthur St. Clair (Philadelphia: Jane Aitken, 1812), 29; “Extract of a letter from Colonel ____, Commanding Officer of a Frontier County, to a Member of Congress—dated Lexington, January, 1792,” Dunlap’s American Daily Advertiser,February 10, 1792, cited in Papers of Washington, 10:156-157. [36]“Biographical Sketch,” Military and Naval Magazine,8; Wiley Sword, President Washington’s Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press), 193; “From Robert Rutherford,” Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:97-100. John Darke is not included on Ebenezer Denny’s list of officers wounded and killed in the battle. (Denny, Military Journal, 172-173.) Darke’s third son, Samuel, died four years later. [37]“From Robert Rutherford,” March 13, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:97; “To Henry Lee,” June 30, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:506-509. [38]“From William Darke,” circa April 25, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:314-315; “From Henry Lee,” June 15, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:455-457. [39]“To Henry Lee,” June 30, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:506-509. [40]“To Henry Lee,” June 30, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:506-509. [41] A Collection of All Such Acts of the Virginia General Assembly of Public and Permanent Nature as are Now in Force(Richmond: Samuel Pleasants, Jr. and Henry Pace, 1803), 282, 310; Brent Tarter,"William Darke (1736–1801)," Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia (1998– ), published 2015 (http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Darke_William, accessed January 14, 2017); Don Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 184, citing “Morgan’s militia commission” in the Myers Collection, New York Public Library. The General Assembly transferred the power to appoint future militia generals to the governor on December 10, 1793. [42]“Henry Lee, Governor to General Wood, Lieutentant-Governor,” September 19, 1794, Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 7: 318. Henry Lee was the father of Robert E. Lee, who was born in 1807. [43]Daniel Morgan to the Governor, September 16, 1794, Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 7: 315-316, 341-342. [44]George Washington to Henry Lee, October 20, 1794, Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 7:356. [45]William Findley, History of the Insurrection in the Four Western Counties of Pennsylvania in the Year MDCCXCIV (Philadelphia: Samuel Harrison Smith: 1796), 148. See also Hugh H. Brackenridge, Incidents of the Insurrection in the Western Parts of Pennsylvania, in the Year 1794 (Philadelphia: John McCulloch, 1795), 61. [46]Findley, History of the Insurrection, 148. [47]Findley, History of the Insurrection, 321. [48]Tarter, “William Darke.” [49]Henry Holcombe, “A Sermon Occasioned by the Death of Lieutenant-General George Washington; first delivered in the Baptist Church, Savannah, Georgia, January 19, 1800, and now published, at the request of the Honorable City Council” (Savannah: Seymour and Woolhopter, 1800), (text posted at www.consource.org/document/a-sermon-occasioned-by-the-death-of-washington-by-henry-holcombe-1800-1-19/). Read More: Darkesville: A Name Born of Tragedy More from The 8th Virginia Regiment On New Year’s Day, 1783, the senior-most major of the Virginia Continental Line wrote to the commander in chief asking for permission to resign his commission. David Stephenson had been in the army for seven years, beginning as a Captain of an Augusta County company in the 8th Virginia Regiment. His service had, in monetary terms, cost him everything. “When I entered the service my fortune was very small and is now entirely expended,” he wrote. “Extravagance has been no cause of my present situation, nor is it from interested motives I would now wish to retire; but it is as really out of my power to equip myself decently as it is to purchase the Indies.” Stephenson was, in fact, not far from home. He wrote to Washington from Winchester, Virginia where he may have been guarding prisoners or performing other duties in the Shenandoah Valley’s largest town. Stephenson had traversed the former colonies from New York to Georgia, survived battles, malaria and capture by the enemy. Penniless, he told Washington that he could not even afford to clothe himself. “Conscious that your Excellency will never wish to continue an officer in Service whose appearance must be so inferior to his rank, I rest satisfied of your approbation to retire.” The war was essentially over, anyway. Within months, there would be a treaty to formalize it. When Stephenson returned home he was about 38 years old. Before the end of the year he married Mary Davies. They were married for 27 years before he died about 1810. Mary died in 1815. An unproven account that they had one son together is challenged by Mary’s will, in which all of their property was given to nieces and nephews from both sides of the family. She also directed that their slaves were “to be liberated and transported to some free State.”

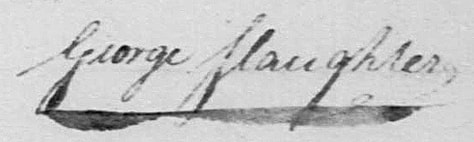

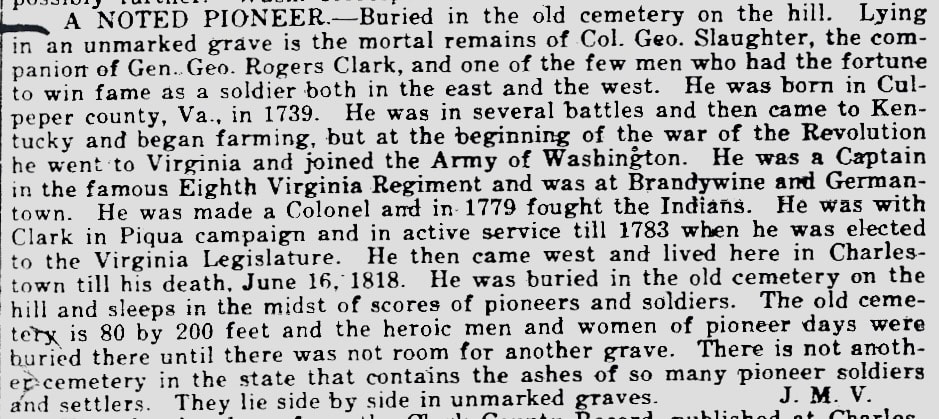

An 8th Virginia soldier like Captain George Slaughter might have seen the Revolution as just one chapter in a six-decade fight with the Indians for control of Kentucky and Ohio. The territories were the scenes of nearly constant bloodshed from the defeat of General Edward Braddock in 1755 to the defeat of Shawnee chief Tecumseh in 1813. After more than two decades of intermittent barbarity, Slaughter and his comrades suffered from no moral anguish when it came to killing Indians.

A decade later, he participated in Dunmore’s War. This was another campaign, led by the royal governor of Virginia, to “pacify” the Indians. After a lengthy and bloody battle at Point Pleasant on the Ohio River, the Virginians were victorious. Slaughter’s unit, however, reportedly arrived too late to participate in the fighting. "They had not the satisfaction of carrying off any of our men's scalps, save one or two of the stragglers," he wrote to his brother. "Many of their dead they scalped, rather than we should have them; but our troops scalped upwards of twenty of their men, that were killed first." His father-in-law was killed in the battle. After the campaign ended, Slaughter explored Kentucky for a while and planted corn—perhaps to lay claim to some land. A year later, in 1775, he may have helped recruit one of the first companies for the famous Culpeper Minutemen. The minute battalions were replaced in 1776 by additional full-time regular regiments, including the 8th Virginia. Slaughter recruited a company in Culpeper County. He remained with the regiment through Charleston and Brandywine and was then promoted to major of the 12th Virginia just before the Battle of Germantown. At Valley Forge, in December of 1777, he learned that his family had lost their house in a fire. That, and a smallpox epidemic (against which he, but not his family, had been inoculated), prompted him to request a furlough from General Washington. The furlough was turned down. He resigned his commission on December 23 and headed home to Culpeper. On February 1, he contritely wrote to Washington begging to be reinstated. “If my reenstation can take place with propriety,” he wrote, “it will afford me great satisfaction; if not, I hope I can Acquiesce without murmuring.” The request was denied. Virginia authorized four battalions of six-month volunteers in June 1778. These were state (not Continental) soldiers intended to reinforce Washington's army. Slaughter was chosen to lead one of the battalions. However, in August Congress advised the Commonwealth that the battalions would not be needed and the half-recruited units were disbanded. It is possible, however, that Slaughter's battalion was ultimately repurposed rather than dissolved. After George Rogers Clark’s important victories in the west, Maj. John Montgomery returned to Virginia with dispatches. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and ordered to recruit additional forces to reinforce Clark. On January 1, 1779, Gov. Patrick Henry drafted orders for Clark based on decisions of the state legislature. “They have directed your battalion to be completed, 100 men to be stationed at the falls of the Ohio under Major Slaughter, and one only of the additional battalions to be completed. Major Slaughter’s men are raised, and will march in a few days, this letter being to go by him. The returns which have been made to me do not enable me to say whether men enough are raised to make up the additional battalion, but I suppose there must be nearly enough. This battalion will march as early in the spring as the weather will admit.”

Slaughter’s participation in Shelby’s campaign is circumstantially supported by the fact that he was once again recruiting in Virginia in the fall of 1779. Slaughter recruited 150 men who were sworn into the service in mid-December when they headed west. They made it as far as Redstone Fort in Pennsylvania before getting bogged down by snow. In the spring, they made it to Fort Pitt and boated downstream to the falls of the Ohio River. This site is now Louisville, Kentucky, a city of which Slaughter is considered a founder—he was one of the original trustees.

Safety was not his only problem. He also reported, “We are here without money, Clothing, or any thing else scarsely to subsist on. By the fault of the Commissaries, Hunters or I cannot tell who upwards of One hundred and Thirty Th[ousan]d weight of meat was intirely spoiled and lost.” Things improved for Slaughter and his neighbors from there. This can be seen in a letter his old 8th Virginia commander Colonel Abraham Bowman (who moved to Kentucky in 1779) sent home on October 10, 1784. Bowman wrote to a brother that "General Clark has laid off a town on the other side of the Ohio, opposite the falls, at the mouth of Silver creek, and is building a saw and grist mill there." This was Clarksville, in Clark County, Indiana. The same year, Slaughter was elected to the Virginia legislature. In 1792 Kentucky became its own state.

(Revised and updated, December 22, 2019 and June 15, 2022.) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

He then led the Fincastle (Kentucky) County company for the 8th Virginia in 1776. After his company was decimated by malaria in south, he was detached to lead a new company in Morgan’s Rifles and took part in the first major American victory of the war at Saratoga. After the war, he served in the legislatures of Virginia and Kentucky (after it separated from Virginia) and served in the Kentucky militia as a colonel. In 1805 he married the widow of his neighbor and friend, Benjamin Logan.

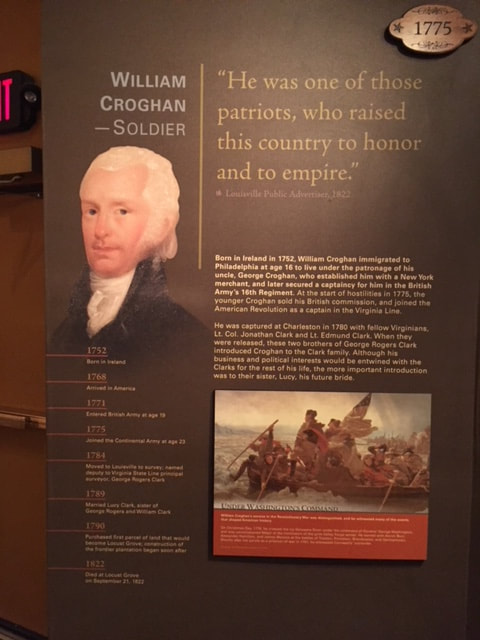

I drove by the creek one more time and looked high up on the bluff on the opposite side. Through the trees, I could just make out a monument. Looking on my phone at pictures on FindAGrave.com, I decided it looked like Benjamin Logan’s grave marker. Knox’s grave is up there too, but can’t be seen from the road. The Logan cemetery was cleaned up in 2015. Already “neglected and overgrown” in 1923, it was described in 2015 as “in complete disrepair; you couldn’t even walk through it, you had to spread the trees and the bushes and the vines apart to even get through it.” My search for Knox’s grave is a perfect allegory for the story of the 8th Virginia. The story is out there, but it’s frequently very hard to find. Read More: "James Knox Was There Before Daniel Boone" (8/19/17) (Updated 1/27/21) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment Locust Grove, built by 8th Virginia Captain William Croghan about 1792. Locust Grove, built by 8th Virginia Captain William Croghan about 1792. No other place does more to tell the story of the 8th Virginia Regiment than the house and museum at Locust Grove, near Louisville, Kentucky. It does this almost unintentionally. Locust Grove was the after-war home of Captain William Croghan (who was a major when the war ended). He married the sister of fellow 8th Virginia Captain Jonathan Clark and lived not far from Clark at the fall-line of the Ohio River (Louisville). This was a roughly 400-mile boat ride from his old home at Pittsburgh.For many 8th Virginia men, the opening up of Kentucky was their main reason for fighting in the war. Colonel Abraham Bowman, captains Croghan, Clark, James Knox, and George Slaughter all moved to Kentucky after (or during) the war. So did a large number of the regiment’s junior officers and enlisted men. I have compared this research to a jigsaw puzzle—the compilation of thousands of discrete bits of information from a multitude of sources. It was a bit of a shock, therefore to visit Locust Grove and find a place that seemed in so many ways to be a memorial to the 8th Virginia Regiment and its veterans. It isn’t actually that, of course. I don't think the regiment itself is even mentioned. Much more is said about Croghan's brother-in-law George Rogers Clark. But the museum’s exhibits wonderfully contextualize and illustrate the world of the 8th Virginia, before, during and especially after the war. Croghan was a very important man in Kentucky. He had money, land, and relationships. Much or most of that—including his marriage—came to him through his service in the war. The same could be said for many of his 8th Virginia comrades who prospered in the west. It was in large measure what they fought for during the Revolution: opportunity. |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed