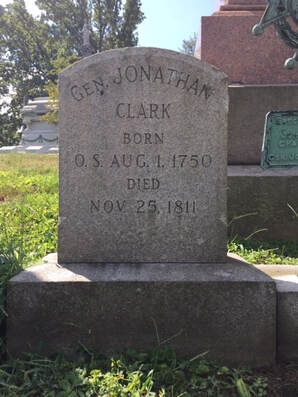

Jonathan and his wife Sarah Hite Clark lie in the center of six Clark family graves fronting a family monument at Louisville's Cave Hill Cemetery. Flags adorn the graves of Jonathan, George, and Edmund, who fought in the Revolutionary War. Their famous younger brother, William, is buried in St. Louis, Missouri. (Author)

29 Comments

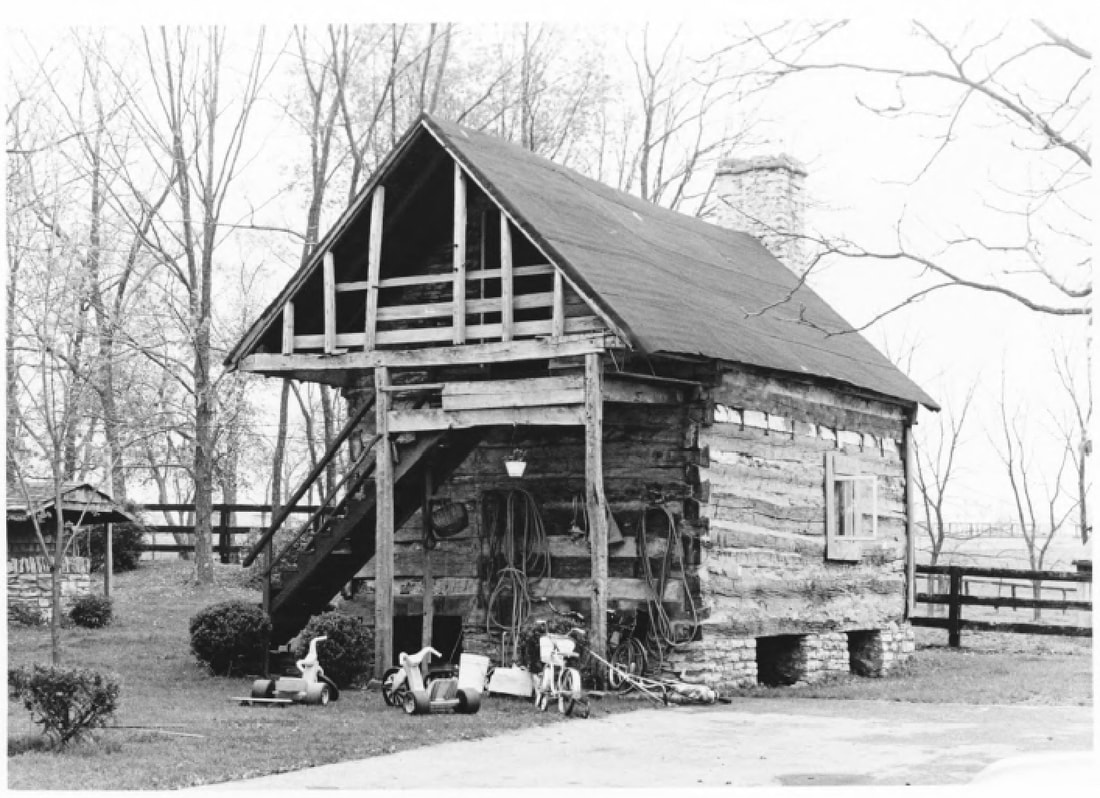

Colonel Abraham Bowman's Kentucky cabin in 2017, as restored circa 2002. Colonel Abraham Bowman's Kentucky cabin in 2017, as restored circa 2002. 8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman’s frontier cabin looks better than has in 200 years. Frontier log cabins, usually built of American Chestnut on stone foundations, were very durable structures. A surprising number of them survive today, including the cabin 8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman built about 1779 or 1780 when he moved to Kentucky. Nevertheless, after two centuries, the Bowman cabin showed signs of deterioration (and alteration) when images of it were submitted to the National Park Service in 1979. Bowman and his brothers are remembered as accomplished equestrians, reportedly known back in the Shenandoah Valley as the “Four Centaurs of Cedar Creek.” Appropriately, most of his land in Kentucky is now part of one of the most important equestrian facilities in the world. His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Emir of Dubai and Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates, is a horse enthusiast and owner of a global thoroughbred stallion operation which stands stallions in six countries. Soon after acquiring the property in 2000, Sheikh Mohammed had the Bowman cabin repaired and restored, along with other properties built long ago for Bowman’s children. The unique cabin, which features a basement and an exterior staircase to a second floor, has never looked better. The most notable change from the restoration is the reorientation of the exterior stairs, presumably to their original position and providing more headroom over the basement stairs.

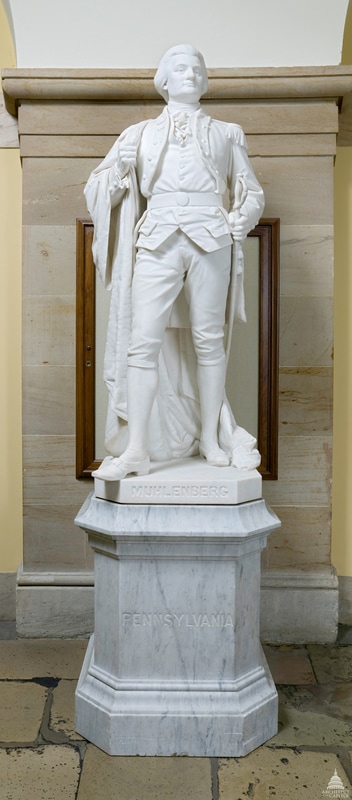

The second-most commonly-seen image is probably the statue that stands in the United States Capitol, one of two statues representing the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. This statue, which was created in 1889 by Blanche Nevin, hardly resembles the Trumbull and Martin Gallery portraits. It depicts Muhlenberg as the new colonel of the 8th Virginia Regiment, removing his pastor’s robe to reveal a military uniform. It appears to be a Continental Army uniform, which would be incorrect--the 8th Virginia was a Provincial Virginia regiment for the first several months of its existence. He may, in fact, have worn the same hunting shirt that his junior officers and enlisted men wore. This statue is the prototype for countless other images of Muhlenberg as a dashing young pastor surprising his congregation by revealing a uniform under his cloak. Neither his commission nor his uniform were in fact a surprise, though there is no reason to doubt the sermon.

Trumbull worked hard to make his depiction of the people in his history paintings as accurate as possible. He wrote that “to transmit to their descendants, the personal resemblance of those who have been the great actors in those illustrious scenes” was one of the goals of his patriotic painting. A war veteran from a prominent Connecticut family, Trumbull knew many of his subjects personally.

(Updated 9/17/21) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

After a prisoner exchange he immediately recruited a regiment of frontier militia and was present for the victory at Yorktown. An Ohio county and a West Virginia town are named after him. He was well-known to George Washington, who personally asked him to serve in General Arthur St. Clair’s army of 1791. Washington clearly knew Darke and respected him. They may have served together in General Braddock’s army in 1755—though this is unproven and seems unlikely. If they served together in the French and Indian War it was more likely during the less well-known frontier conflicts that followed, when Darke served as a ranger. After the revolution, they had a business relationship though the Potomac Company, formed by Washington and others to make that river navigable. Darke Visited Mount Vernon in 1786 and 1787. Washington visited with Darke near the latter’s home close to Harper’s Ferry in 1790. In 1791, Washington wrote to Darke asking him to recruit officers for St. Clair’s army in advance of the campaign to pacify the Indians in Ohio. In that letter Washington bluntly and unapologetically told Darke that he was his third choice to command a regiment—pending a reply from his second choice (his first choice was “Light Horse Harry” Lee, who declined). Intriguingly, what may be the best evidence of a close (but certainly unequal) relationship between Darke and Washington is a gift. According to longstanding tradition—apparently perpetuated by descendants of Washington’s nephew—Darke presented Washington with a sword. The date of the presentation is unknown, but it is believed by at least one researcher to have been worn by Washington at his presidential inauguration. The sword itself is real—it is on display at the Washington’s Headquarters Museum in Morristown, New Jersey. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Croghan commanded the remnants of a 140-man detachment that included his own company from Pittsburgh, and another seventy 8th Virginia soldiers who had missed the spring rendezvous at Suffolk, Virginia. For the year, Croghan's men were attached to the 1st Virginia Regiment. That regiment's field officers (colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major) were all sick or wounded, so a man of Croghan's own rank was in command: Capt. John Fleming from Goochland, Virginia. In a week, even Fleming would be dead. There is good reason to think that Croghan was also too sick to command his men and that Lt. Abraham Kirkpatrick (also from Pittsburgh) stepped up to lead. The crossing and the all-night march to Trenton were arduous. The bloody footprints in the snow we learned about in school were very real. Men who sat too long on the way to Trenton froze to death. But the suffering resulted in a victory over the Hessians that revived the American cause. “[B]eat the damn Hessians and took 700 and odd prisoners,” wrote Sgt. Thomas McCarty in his diary. The march back was even worse than the approach. A week later, at the battle of Princeton, only a handful of Captain Croghan's men were fit for service. At Trenton, Croghan's men fired on the enemy just yards in front of General Washington and alongside the soldiers of Colonel George Weedon's 3rd Virginia. Their victory, though small in military terms, revived a dying cause. Afterward, the overconfident British became more cautious and Washington found a tactical model for victory against an enemy that was better trained and equipped. Thereafter, Christmas would always carry a special meaning for those who were there. After the war George Weedon wrote a song that was sung each year at a large party he held at his home in Virginia. The song was remembered by the orphaned son of Gen Hugh Mercer, who died at Princeton. The younger Mercer knew Weedon as his “uncle and second father.” He recalled that for “many years after the Revolution my uncle celebrated at ‘The Sentry Box’ (his residence, and now mine) the capture of the Hessians, by a great festival—a jubilee dinner, if I may so express myself—at which the Revolutionary officers then living here and in our vicinity, besides others of our friends, were always present. It was an annual feast, a day or so after Christmas Day, and the same guests always attended. …I was young, and a little fellow, and was always drawn up at the table to sing ‘Christmas Day in ’76'…. It was always a joyous holiday at ‘The Sentry Box.’” Christmas Day in '76 On Christmas Day in seventy-six Our ragged troops, with bayonets fixed, For Trenton marched away. The Delaware ice, the boats below, The light obscured by hail and snow, But no signs of dismay. Our object was the Hessian band That dare invade fair Freedom’s land, At quarter in that place. Great Washington, he led us on, With ensigns streaming with renown, Which ne’er had known disgrace. In silent march we spent the night, Each soldier panting for the fight, Though quite benumbed with frost. Green on the left at six began, The right was with brave Sullivan, Who in battle no time lost. Their pickets stormed; the alarm was spread The rebels, risen from the dead, Were marching into town. Some scampered here, some scampered there, And some for action did prepare; But soon their arms laid down. Twelve hundred servile miscreants, With all their colors, guns, and tents, Were trophies of the day. The frolic o’er, the bright canteen In center, front, and rear, was seen, Driving fatigue away. And, brothers of the cause, let’s sing Our safe deliverance from a king Who strove to extend his sway. And life, you know, is but a span; Let’s touch the tankard while we can, In memory of the day. [Updated 12/25/20] More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

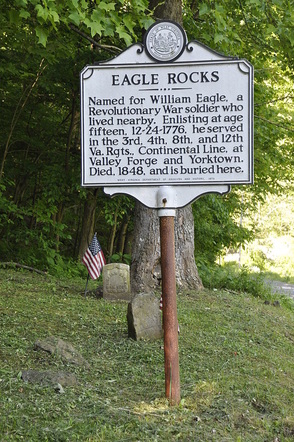

Despite his evidently very rough edges, Kirkpatrick became part of the post-war Pittsburgh elite. He co-founded the Bank of Pittsburgh and ran an early steel mill. His grandson Abraham Kirkpatrick Lewis was a pioneer in the Pittsburgh coal business, shipping coal on flat boats all the way to new Orleans. In 1794, President George Washington sent Abraham Kirkpatrick several bottles of imported wine to thank him for helping put down the Whiskey Rebellion. One bottle survives, having been kept by the family for over two centuries. Its contents are now evaporated into a dry sediment. It was put up for auction a few years ago but didn’t sell. Details about the object, including a high-definition image, can be seen at the Skinner auction house website. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment On December 14, 1776, the 8th Virginia’s Sergeant Thomas McCarty wrote in his diary, “I lay in camp and the excessive cold weather made me very unwell.” He and the rest of Washington’s army lay shivering on the west bank of the Delaware River, temporarily safe from the enemy who had chased them all the way from New York. This was the Revolution’s darkest time. Washington was losing. Badly. His troops were barefoot and hungry, and most of their enlistments were about to expire. People were giving up. Richard Stockton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, swore allegiance to the King. Many others believed the cause was lost. For the enlisted men, the immediate problem was the historically cold December weather. McCarty had frostbite. “I had great pain with my finger,” he wrote on December 9, “as the nail came clean off.” For shelter, he made a hut out of tree branches. It burned down on the thirteenth, along with nearly everything he had. McCarty and the other men in Captain William Croghan’s company of Pittsburgh men had had it rough. They were separated from the rest of the regiment by hundreds of miles because they had missed the spring rendezvous at Suffolk, Virginia. Now, freezing in the snow after being hounded across New Jersey by the enemy, things looked very bleak. In two weeks, most of the army would go home—but not Croghan's men. Soldiers from Virginia (including Pittsburgh) were on two year enlistments. On December 14, 1776, it looked like they would remain behind only to see the Revolution’s last gasp. But things were about to look very different.  In my October 29 post about William Eagle, I wrote that he "enlisted in the 8th Virginia on Christmas Eve, 1776" and that he "was one of the first to sign up when the regiment came limping back to Virginia from its encounters with redcoats and ... malaria in South Carolina and Georgia." I gave him credit for being "one of the few who enlisted during the Revolution’s darkest hour." Well, it's not true. His pension says it's true and the West Virginia historic marker that stands next to his grave says it's true. But they are both wrong. First, His name appears nowhere in the muster or pay rolls for 1777, and the "commencement of pay" date for on his first pay roll entry is February 1, 1778. Second, His pension affidavit claims that he "enlisted for the term of three years, on or about the 24th day of December in the year 1776, in the state of Virginia in the Company commanded by Captain Stead or Sted or Steed, in the Regiment commanded by Colonel Nevil or Neville." Colonel John Neville (no known relation to me) commanded the regiment after it was folded into the 4th Virginia in the fall of 1778. Had Eagle enlisted in the regiment in December of 1776 and joined it in January of 1777 he would certainly have mentioned Colonel Abraham Bowman, who became a "supernumerary" officer when the regiment was folded into others in the summer of 1778 and released from service in the fall. Eagle served under Bowman only for a little while and, consequently, did not mention him. Eagle got the names right (Neville and Steed), but the year wrong. Third, the term of his enlistment is consistently recorded as for 3 years or the length of the war (which ever was shorter). Soldiers who enlisted in 1777 or later enlisted under these terms. Virginia soldiers who enlisted in 1776 signed up for two years. (Someone might argue that a date so late in the year might have been treated differently, but I'm not aware of any examples of this.) The date of his enlistment is not recorded anywhere in the surviving official records. From the evidence, however, it seems certain that he in fact enlisted "on or about the 24th day of December" in the year of 1777 (not 1776), and joined the regiment at Valley Forge about a month later. Eagle is not the only veteran who got the dates of his service wrong when applying decades later for a pension. It is an understandable error. The State of West Virginia might, however, want to invest in an updated marker.  The Marquis de Lafayette with the 8th Virginia. (Frank Schoonover) The Marquis de Lafayette with the 8th Virginia. (Frank Schoonover) The 8th Virginia was composed of ten companies. Each one was supposed to have 68 enlisted men led by four officers (captain, 1st lieutenant, 2nd lieutenant, and ensign). At least one overenlisted and one underenlisted. The overall regiment was commanded by three field officers (colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major) assisted by several staff officers (chaplain, adjutant, surgeon, surgeon's mate, paymaster, and quartermaster). One inherited company was composed men on 1-year enlistments that began in December of 1775. The other nine companies served 2-year enlistments, beginning in the spring of 1776 and ending at Valley Forge in the spring of 1778. An 11th company was raised to replace the 1-year men in 1777. Replacements recruited in 1777 served 3-year enlistments. The 8th existed from December 13, 1775 when it was authorized by the Virginia Convention, to September 14, 1778 when it merged with the 4th Virginia and took that number. I have posted an outline of the regiment's structure, listing officers and some enlisted men (when I have written about them or heard from descendants). This is not intended to be a full "roster" of the regiment, but rather a look at its structure, origins, and organization. The names of known descendants are in brackets after a soldier's name. An alphabetical lift of descendants is available on The Family Page. If you would like to be identified with your ancestor, please send an email over the web form. Your email address will be linked from your name only if you specifically request it.  A historic marker in Pendleton County, West Virginia tells the story of fifteen year-old William Eagle, who enlisted in the 8th Virginia on Christmas Eve, 1776. This was the Revolution's darkest hour. Washington's dwindling army had fled from the British across New Jersey and was now huddling, frozen by fear and cold on the West Bank of the Delaware. At a moment when few were willing to enlist, this teenage patriot stepped forward. Except it isn't true. Eagle's pension gives the same date that appears on the sign, but they are both wrong. The sign probably takes its date from the pension. As far as we know, Eagle served honorably and well. But he didn't enlist until December of 1777 when he was sixteen years old. The evidence is clear. First, His name appears nowhere in the muster or pay rolls for 1777, and the "commencement of pay" date on his first pay roll entry is February 1, 1778. Second, His pension affidavit claims that he "enlisted for the term of three years, on or about the 24th day of December in the year 1776, in the state of Virginia in the Company commanded by Captain Stead or Sted or Steed, in the Regiment commanded by Colonel Nevil or Neville." Colonel John Neville (no known relation to me) commanded the regiment after it was folded into the 4th Virginia in the fall of 1778. Had Eagle enlisted in the regiment in December of 1776 and joined it in January of 1777 he would certainly have mentioned Colonel Abraham Bowman, who became a "supernumerary" officer and was released from service when the regiments merged. Eagle served under Bowman only for a short while and, consequently, did not mention him. Eagle got the names right (Neville and Steed), but the year wrong. Third, the term of his enlistment is consistently recorded as for 3 years or the length of the war (which ever was shorter). Soldiers who enlisted in 1777 or later enlisted under these terms. Virginia soldiers who enlisted in 1776 signed up for two years. (Someone might argue that a date so late in the year might have been treated differently, but I'm not aware of any examples of this.) The date of his enlistment is not recorded anywhere in the surviving official records. From the evidence, however, it seems certain that he in fact enlisted "on or about the 24th day of December" in the year of 1777--not 1776--and joined the regiment at Valley Forge about a month later. Eagle is not the only veteran who got the dates of his service wrong when applying for a pension decades later. It is an understandable error for an old man to make. The State of West Virginia might, however, want to invest in an updated marker. So what happened to William Eagle? After nearly two years of service he was “discharged for inability” on September 1, 1779. Tradition has it that he had a broken arm. Whatever his injury was, it saved him capture following the surrender of the Virginia Line after the Siege of Charleston in May of 1780. William Eagle’s grave is by Eagle Rocks, a steep peak near the headwaters of the Potomac in West Virginia’s remote Smoke Hole Canyon. Ross B. Johnston wrote in his book West Virginians in the Revolution that the veteran named his son George Washington Eagle, and he nearly lost his life one day climbing his namesake peak in an attempt to capture some baby eagles. (Revised December 21, 2019)

|

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed